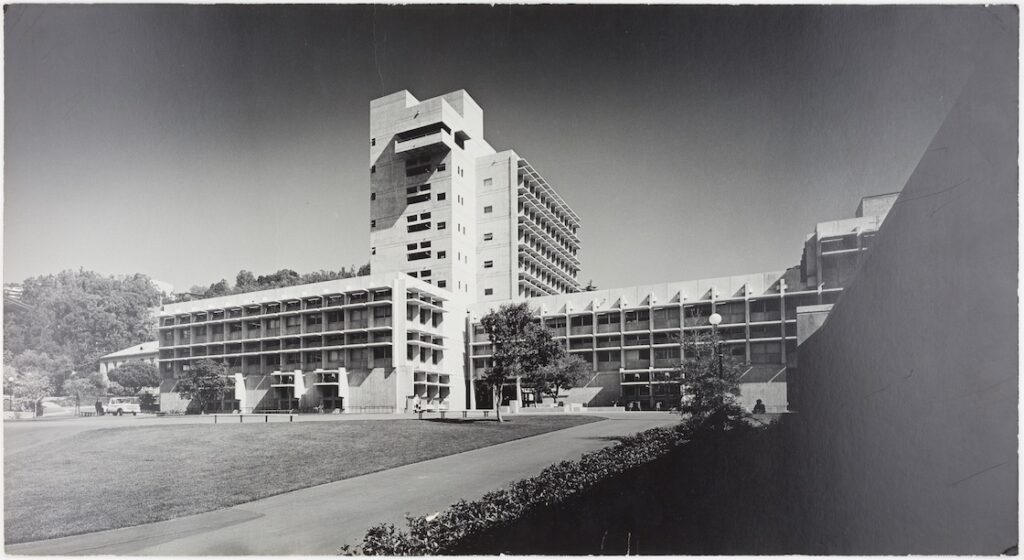

Bauer Wurster Hall

After the founding of the College of Environmental Design in 1959, the new entity needed a new home. Planning began in the late 1950s, and the building welcomed its first class of students in 1964.

Dean William Wurster championed the idea that the building should be designed by members of the architecture faculty, as hiring an outside architect would indicate a lack of faith in the faculty’s skills. Distrusting unanimity, he relished the idea of having three architects with totally different points of view. His choices were Vernon DeMars, Donald Olsen, and Joseph Esherick.

For two years, from 1958 to 1960, the architects met with a faculty building committee and Louis DeMonte, the campus architect. As many as 20 schemes were developed as departments explored circulation and orientation and quibbled over space allocations and locations, while the different architects argued from their varying perspectives. One point of agreement was that the new building should have a courtyard, as a carryover from the cherished courtyard in the “Ark,” the previous architecture building (now North Gate Hall).

The building’s stark, austere appearance was intentional. Wurster wanted the designers to create what he called a ruin, a building that “achieved timelessness through freedom from stylistic quirks.” The bold choice of concrete reflected both economic realities and the modernist aesthetics of the time — for instance, Paul Rudolph’s Yale School of Architecture, also concrete, had recently been finished.

“Wurster and his handpicked architects didn’t want anything romantic, or sentimental — they hated the idea of ‘making pretty buildings,'” explains Betsy Frederick-Rothwell, curator of the Environmental Design who organized an exhibit on the building. “They wanted a serious building.”

That generation of designers, formed during the 1930s and 1940s, understood architecture, landscape architecture, and city planning as sober professions that were central to solving big social problems. They had faith that shaping the built environment could shape society for the better.So the design team set out to build a functional, rational building, both in terms of structure and use.

“They wanted a building that would be timeless, that wouldn’t influence architecture students toward one style or another,” says Frederick-Rothwell. “It was intentionally imperfect, or unfinished, a sort of infrastructure or shell open to limitless possibilities.”

The building was extensively renovated with architectural and seismic improvements that were completed in 2003.