“A ruin that no regent would like”: The making of Bauer Wurster Hall

A new exhibition traces the rich history of UC Berkeley’s Bauer Wurster Hall, which has shaped generations of architects.

A campus tour guide, nimbly walking backwards, gestures towards the concrete building that is home to the College of Environmental Design: “Isn’t it ironic that the architecture building is the ugliest on campus?”

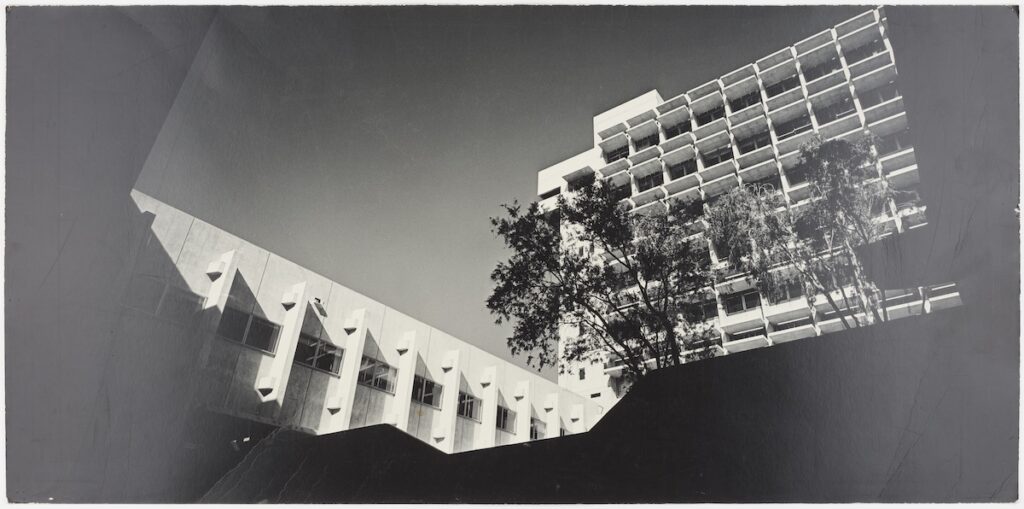

Whether or not you agree with that oft-heard aesthetic assessment — admirers point to the obvious influence of two of the best-known and beloved 20th-century architects, Louis Kahn and Le Corbusier — you might wonder, “Why does Bauer Wurster Hall look so different from other campus buildings?”

That’s what Betsy Frederick-Rothwell, the curator of the Environmental Design Archives, set out to answer with the exhibition Finished-Unfinished: The design of Bauer Wurster Hall, on view through October 8 in the Environmental Design Library. Comprising drawings, photographs, documents, and other artifacts drawn primarily from the archives’ collection, the exhibition in the library’s Judith Stronach / Raymond Lifchez Exhibit Cases traces the building’s origins and subsequent history.

“There are so many juicy behind-the-scenes stories,” says Frederick-Rothwell, who credits Professor Emeritus Stephen Tobriner and the late architectural historian Sally Woodbridge with unearthing much of the building’s past. “Conflicts among the architects about design directions, departments jockeying for prime space in the building, accusations that the presentation drawings ‘tricked’ the UC Regents into approving the final design — it was fascinating to research.”

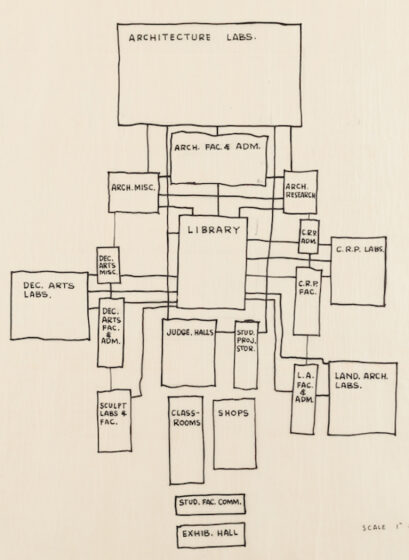

The story of Bauer Wurster Hall begins in 1958, when Founding Dean William W. Wurster appointed faculty members Vernon DeMars, Joseph Esherick, and Donald Olsen to design a building to house the new College of Environment Design (which brought together architecture, landscape architecture, city and regional planning, and decorative arts under one administrative unit and one roof).

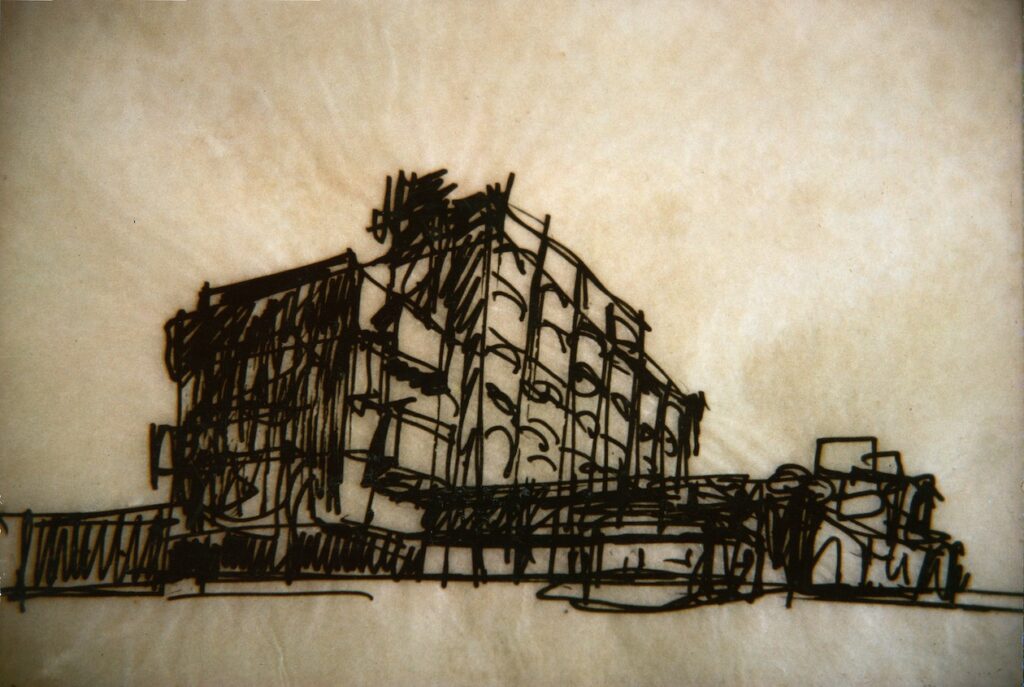

“We discovered that the building’s stark, austere appearance was intentional,” explains Frederick-Rothwell. “Wurster and his handpicked architects didn’t want anything romantic, or sentimental — they hated the idea of ‘making pretty buildings.’ They wanted a serious building.”

That generation of designers, formed during the 1930s and 1940s, understood architecture, landscape architecture, and city planning as sober professions that were central to solving big social problems. They had faith that shaping the built environment could shape society for the better.

So the design team set out to build a functional, rational building, both in terms of structure and use. (Or at least two of the architects embraced this goal; Wurster had purposely selected faculty with different design philosophies, believing it would yield a superior result: “at least they can work at cross-purposes together,” he quipped.)

“They wanted a building that would be timeless, that wouldn’t influence architecture students toward one style or another,” says Frederick-Rothwell. “It was intentionally imperfect, or unfinished, a sort of infrastructure or shell open to limitless possibilities.”

Of course, in the years since the building’s completion in 1964, it has been labeled with a style: Brutalism. Named for their characteristic raw concrete material (béton brut, in French), Brutalist buildings popped up across campuses and urban centers throughout the 1960s. Much maligned in the following decades, the style has gained a new appreciation, even a cult following, in recent years.

The exhibition also reveals that despite the functionalist approach cited by the architects — the drafting desks Olsen designed for the architecture studios determined the spatial module — sentiment did creep in. The monumental staircase dominating the lobby creates a lofty entry sequence (even if it’s not as grand as DeMars had hoped) and the rear courtyard, despite its asphalt surface, was specifically intended to recall the much-loved brick-lined version the Department of Architecture had left behind in North Hall.

Finished-Unfinished doesn’t end with the building’s rich origin story. It goes on to document key moments in Bauer Wurster Hall’s history, including the takeover of many of its spaces in the early 1970s for the production of antiwar protest posters and the renovation of the courtyard 20 years ago that realized the original intention of brick paving.

The exhibition concludes with the latest architectural intervention, the construction of the Digital Fabrication Lab by Mark Cavagnero Associates, and a project to re-create the building in virtual reality — clear signs of the advent of a new era in architectural design. It makes you wonder what an AI would generate if it followed Wurster’s instructions to his architects: design “a ruin that no regent would like.”

The exhibition continues through October 8. Check the library website for hours.

Related events

Thursday, Aug 17 12:15–1 PM

Curator Walk-Through