About CED

The College of Environmental Design (CED) stands among the nation’s top environmental design schools. It is one of the world’s most distinguished laboratories for experimentation, research, and intellectual synergy. The first school to combine the disciplines of architecture, planning, and landscape architecture into a single college, CED led the way toward an integrated approach to analyzing, understanding, and designing our built environment.

CED was also among the first to conceptualize environmental design as inseparable from its social, political-economic, and cultural contexts. Its faculty and students have always seen environmental design as an exploratory spatial practice, aimed at creating forms of building, landscape, and urban plans that have yet to be imagined. At the same time, CED has historically emphasized environmental design as a profoundly ethical practice, co-produced through dynamic engagements with diverse communities, workers, businesses, and policy-makers.

Today’s students have inherited unprecedented global challenges that could not have been foreseen when the college was founded in 1959. This legacy will require radically new ways to fashion the buildings, places, and landscapes that harbor our diverse ways of life. The mission of the college is to produce creative and skilled professionals to help craft built environments — ecologically sustainable and resilient, prosperous and fair, healthy and beautiful — whose logic, form, and materials we as teachers cannot yet conjure. We guide students toward a critical understanding of cities around the world, their architectures and landscapes, and their many layers of meaning. We educate students in the art of designing well-loved places that both nurture our senses and challenge our imaginations. And we help students not only to acquire technical expertise, but also to develop transcendent ways of seeing and refiguring the built environment.

A common thread linking most of CED’s programs is the design studio experience, involving deep immersion in theory, technology, and real-time practice for diverse domestic and international clients. In the studio, fledgling designers take flight, becoming visual thinkers, critical observers, and systems scientists, often working with faculty and classmates from across the college’s departments and programs. This intense, interactive learning arena is the hallmark of a CED education, offering an unparalleled learning environment located at one of the nation’s top public research universities.

Our History

In the mid-20th century, no university in the United States had combined the disciplines of architecture, landscape architecture, and planning under one academic umbrella. Two of UC Berkeley’s many game-changing contributions to environmental design were to help develop the actual concept of environmental design, and then to refine it in a college that included all three design and planning disciplines, integrating their knowledge and contributions in a way that helps to shape the larger environment.

The idea for such an integration at Berkeley came from William W. (“Bill”) Wurster, the dean of UC Berkeley’s School of Architecture, and Catherine Bauer Wurster, a housing reform expert who taught in the architecture school.

Wurster became the founding dean of the college and Bauer Wurster was later appointed associate dean.

This idea was radical for some, and University President Gordon Sproul, when approached with the idea, wondered if it was really necessary when things seemed to work just fine as they were. Committees formed, discussions stretched on and on, departments fought to keep a level of independence from one another while combining forces. The final approval from UC Berkeley’s Academic Senate came in 1959. In the meantime, the name “environmental design” was agreed upon only because no one could come up with a better option that kept all three departments on equal footing. Both Wurster and Bauer initially thought the name was pretentious, but in the end it stood.

The new entity with its new name needed a new home. Planning for what would later be named Wurster Hall began in the late 1950s, although the building was not completed until 1964. Wurster championed the idea that the building should be designed by members of the architectural faculty, as hiring an outside architect would indicate a lack of faith in the faculty’s skills. Distrusting unanimity, he relished the idea of having three architects with totally different points of view. His choices were Vernon DeMars, Joseph Esherick, and Donald Olsen.

For two years, from 1958 to 1960, the architects met with a faculty building committee and Louis DeMonte, the campus architect. As many as 20 schemes were developed as departments explored circulation and orientation and quibbled over space allocations and locations, while the different architects argued from their varying perspectives. One point of agreement was that the new building should have a courtyard, as a carryover from the cherished courtyard in the “Ark,” the previous architecture building (now North Gate Hall).

That was where similarities with the old building ended. Wurster wanted the designers to design what he called a ruin, a building that “achieved timelessness through freedom from stylistic quirks.” The idea of using concrete reflected both economic realities and aesthetics of the time — the Yale School of Architecture had recently been finished and was also built of concrete. While the architects deny they were following any particular style, the building’s design has commonly been labeled Brutalist.

In fall 2020, the college renamed the building Bauer Wurster Hall after finding archival documentation that the building was intended to recognize both William W. Wurster and Catherine Bauer Wurster for their extensive contributions to the founding of CED.

Our Founders

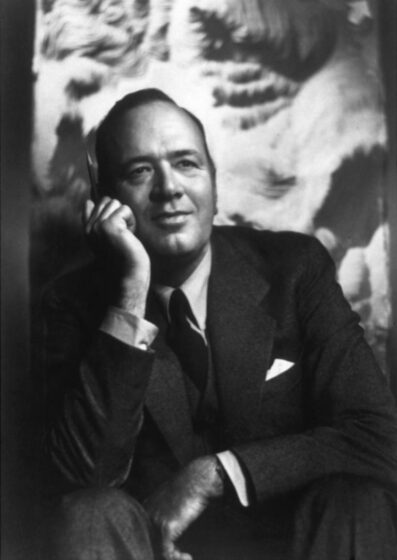

William W. Wurster

An architect and later a professor of city and regional planning, William W. (“Bill”) Wurster (1895–1973) was influenced, among other things, by a Bay Area group of architects, landscape architects, and city planners called Telesis. Telesis had formed in 1939 with the goal of using “a comprehensive planned approach to environmental development, the application of social criteria to solve social problems, and team efforts of all professions that have a bearing on the total environment.” While not a member of the group, he liked its approach.

As a fellow at MIT in the early 1940s, Wurster was instrumental in persuading MIT’s administration to recognize the School of Architecture’s city planning division as a full-fledged and equal department, with the new entity being named the School of Architecture and Planning. He joined UC Berkeley in 1950 as dean of the School of Architecture, where he imagined taking this one step further by adding landscape architecture to the mix. Wurster imagined a college that strengthened each department through joint appointments and interdisciplinary courses, giving students the opportunity to combine studies in the different departments while also focusing on a chosen core area of study.

Wurster had hoped that no University regent would like the building when it was finished, and he got his wish. Although he had proposed not naming the building right away, upon his retirement it was named Wurster Hall in honor of both him and Catherine.

Architectural historian Sally Woodbridge neatly sums up both Wurster’s ideals and the building that was named after him: “As Wurster Hall weathered without mellowing, it reflected Wurster’s opinion that a school should be a rough place with many cracks in it. Perpetually unfinished, Wurster Hall was an open-ended and provocative environment for teaching and questioning.”

Catherine Bauer Wurster

Educator, reformer, and champion of public housing Catherine Bauer Wurster (1905–1964) served and advised three presidents on housing and urban planning strategies — Roosevelt, Truman, and Eisenhower. She drafted legislation for the U.S. Housing Act of 1937, which established the United States Housing Authority (USHA), and authored the influential book Modern Housing (1934), which introduced European modernist housing to American audiences.

Bauer Wurster spent 24 years as an educator, at UC Berkeley (1940–1944, 1950–1964) and Harvard (1944–1950). She became the fifth faculty member and first woman to join the Department of City & Regional Planning at UC Berkeley. A fervent believer in interdisciplinary education, she rewrote the undergraduate curriculum, contributing greatly to its legacy today.

Bauer Wurster was an integral force in pioneering the creation of the College of Environmental Design at UC Berkeley, and would eventually serve as its associate dean.