Campus Architecture

The campus of the University of California, Berkeley has buildings in a great variety of sizes, materials, and styles. In some areas the buildings are placed along symmetrical axial avenues while others are located on curving picturesque pathways. This diversity is the result of 140 years of layered campus plans and changing theories and styles. The College of California started small–a two-acre site in Oakland. Realizing the spatial limitations of this location, the administrators purchased 160 acres of Berkeley farmland in 1860. By 1863, they had hired Frederick Law Olmsted, the creator of New York’s famed Central Park, to design a plan for the new campus. In keeping with the ideals of the City Beautiful Movement, Olmsted’s layout was picturesque and informal with ample open space, paying special attention to natural topography.

In 1867 the College of California was re-chartered as the University of California. The recently appointed Regents set aside Olmsted’s plan, and in 1869 commissioned a new one from San Francisco architect David Farquharson. Farquharson maintained the picturesque nature of Olmsted’s plan, but organized the campus around a central axis dictated by the creeks and terrain and in line with the Golden Gate. The buildings constructed from this period, such as North and South Halls (1873 and 1875), were constructed in the Second Empire Style.

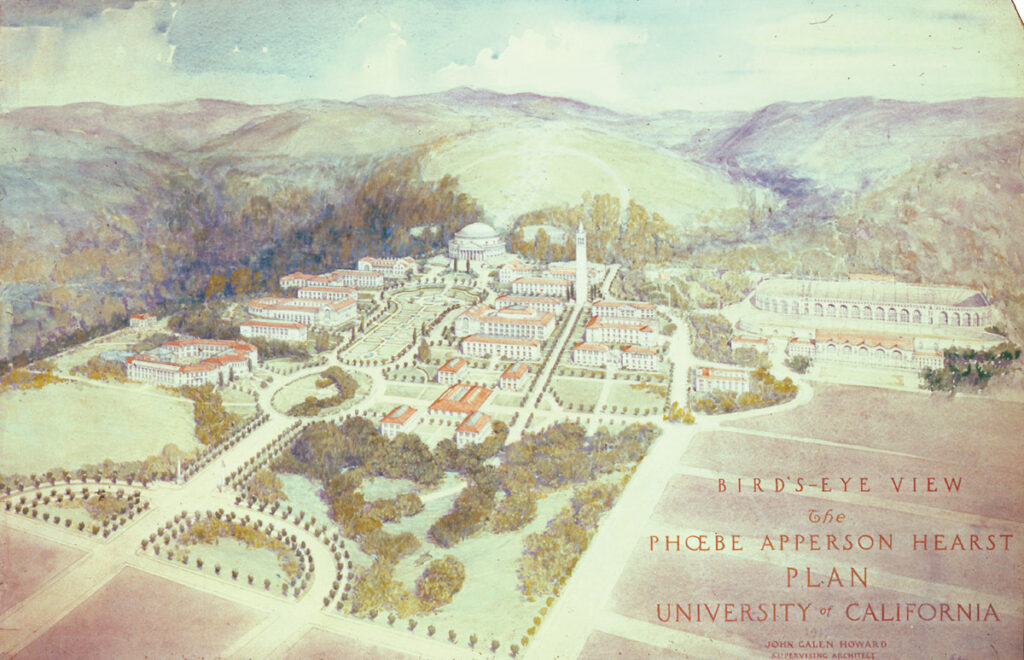

Over the next twenty years, the campus grew slowly. Major buildings were constructed around a nucleus with Campanile Way as the axis. As the Bay Area grew enrollment increased, necessitating the construction of new campus buildings in the 1890s. The Regents believed that the University needed a grand and comprehensive general plan to match its growing size and importance. Compounding the matter, the national taste was moving away from picturesque styles with their asymmetry, informality, and textured materials in preference for the formal planning and classicism taught at France’s architectural school, the Ecole des Beaux Arts. Bernard Maybeck, an instructor of drawing at the University, convinced University benefactor Phoebe Apperson Hearst of the necessity of a comprehensive campus plan. In 1897 she financed an international competition to select an architect. Not surprisingly given the École’s preeminence, a Parisian, École-trained architect named Emile Bénard won first prize. Bénard’s plan for the University was a formal Beaux-Arts composition arranged around a central east-west axis with minor cross-axis. The buildings were to be monumental structures in classical styles built of uniform materials.

Emile Bénard declined to be appointed supervising architect, and in 1901 the position was offered to John Galen Howard, the fourth-place winner of the competition. Although Howard was directed to execute Bénard’s plan without any substantial departure, he made small alterations until the plan was more his than Bénard’s. However, Howard was loyal to the Beaux-Arts character of Bénard’s plan. The only evidence of Olmsted’s original design was the park-like glade at the west edge of campus, and the informal appearance and location of the Women’s Faculty Club (1923) and the Men’s Faculty Club (1903). While Howard was supervising architect, eighteen buildings were constructed including the Hearst Memorial Mining Building California Hall, the Greek Theater, Wheeler Hall, Doe Library, Stevens Hall, and the Campanile.

By the 1920s the administration and Howard had grown at odds over fees and the hiring of Bernard Maybeck and Julia Morgan for a number of buildings financed by William Randolph Hearst. In 1924 Howard was dismissed, and in 1927 George W. Kelham, a well-known San Francisco architect, was hired as his replacement. The early buildings constructed under Kelham, Bowles Hall, McLaughlin Hall, and Giannini Hall – designed by William C. Hays, were simple and classical in appearance and situated according to Howard’s plan. However, the immense size and Moderne Style of the Valley Life Sciences Building in 1930 marked a departure from the scale and style of the previous architecture.

In 1938 San Francisco architect, Arthur Brown Jr., was appointed supervising architect. The pace of construction slowed during the early years of Brown’s tenure, due to the lingering effects of the Great Depression and World War II. Brown held true to Howard’s vision of classical architecture, but given the architectural styles and financial climate of the day, the buildings were minimalist versions. Some of the buildings constructed during Brown’s term include Sproul Hall, Minor Hall, and the Library Annex, now The Bancroft Library. In 1944 Brown created a new general plan which was based on Howard’s design with the addition of numerous new buildings.

After Brown left the University in 1948, no supervising architect was appointed, and the University office of Architects & Engineers assumed that role. In 1955 the Regents approved the formation of the Committee on Campus Planning, comprised of William W. Wurster, the Dean of the College of Architecture, Chancellor Clark Kerr, and Regent Donald McLaughlin. In 1956, in consultation with the Office of Architects & Engineers, their first major project was to create a long-range development plan that treated such issues as parking, the relationship between the city and the University, the preservation of historic buildings, and campus landscaping. One of the many outcomes of this plan was the commissioning of designs by landscape architects such as Thomas D. Church.

The 1960s was a time of incredible growth at the University; the number of students increased from 5000 to 10,000. The enlarged student body required the construction of bigger buildings, and the remodeling of older structures such as Doe Library. As the school grew, the campus was separating into distinct colleges becoming what Kerr called a “multiversity.” To house these departments mammoth modern buildings like Kroeber Hall by Gardner Dailey, Wurster Hall by Vernon DeMars, Joseph Esherick, & Donald Olsen, and Zellerbach Hall by Hardison & DeMars were constructed. Classicism had long since lost favor, and the new buildings were built in a variety of contemporary styles.

Not all were pleased with the demolition of historic buildings, the construction of enormous buildings, and the dismissal of the comprehensive campus plan. In addition charges were leveled that the ad-hoc placement of the new buildings lacked sensitivity – constructed in the 1970s, Evans Hall was both out of scale with the surrounding buildings, and placed in the middle of the central glade, and Moffit Library blocked the main axis of the original campus plan. In answer to these criticisms Chancellor I.M. Heyman set up a new organizational structure for campus space planning in 1980.

In the eighties and nineties issues such as transportation and the relationship with the surrounding city of Berkeley were paramount, including the always thorny issue of the University’s development of People’s Park. In addition the program of remodeling existing buildings such as the Haas Pavilion, formerly the Harmon Gymnasium, and additions to others, like the Valley Life Science Building was continued. New structures, often for support functions, such as the Recreational Sports Facility and the Tang Center were constructed. In 1989 the Loma Prieta earthquake provided campus planners with the need to seismically retrofit many of the campus buildings. The 1990 Long Range Development Plan, by the Campus Planning Office in association with ROMA Design Group, once again sought to cluster program, preserve historic and natural resources, and move development and automobiles to the periphery.

In 2002, the Campus Planning Office developed the New Century Plan (NCP) in association with Sasaki Associates. It provided a comprehensive strategic plan for the University’s capital investment program, setting policies for all future University development of campus buildings and landscape through the middle of the century. Undoubtedly in the future new issues will arise and building and planning styles and theories will continue to change adding to the controversy, complexity, and diversity of the U.C. Berkeley Campus.

For more information go to the UC Berkeley Landscape Heritage Plan.

Selected Bibliography

Berkeley Buildings and Landmarks. Berkeley, Calif.: University of California, Berkeley, 1965.

The Berkeley Campus Space Plan. Berkeley, Calif.: University of California , Berkeley. Buildings and Campus Development Committee, 1981.

Kantor, J.R.K. University Architect, John Galen Howard.Berkeley, Calif.: CU News, 1975.

Partridge, Loren W. John Galen Howard and the Berkeley Campus: Beaux-Arts architecture in the Athens of the West.

Berkeley, Calif.: Berkeley Architectural Heritage Association, 1978. Berkeley Architectural Heritage publication series; no. 2.

Helfand, Harvey. The Campus Guide: University of California, Berkeley. New York, NY.: Princeton Architectural Press, 2002.