Heterogeneous Constructions: Aaron Forrest, Yasmin Vobis, and Brett Schneider talk about their new book with Neyran Turan

How can we embrace heterogeneity — in design, in construction, in teaching, and in the culture of architecture?

On the occasion of the publication of Heterogeneous Constructions: Studies in Mixed Material Architecture (Birkhäuser), Associate Professor of Architecture Neyran Turan spoke with the authors, Aaron Forrest, associate adjunct professor of architecture; Yasmin Vobis, assistant professor of architecture; and Brett Schneider, associate professor of architecture at Rice University.

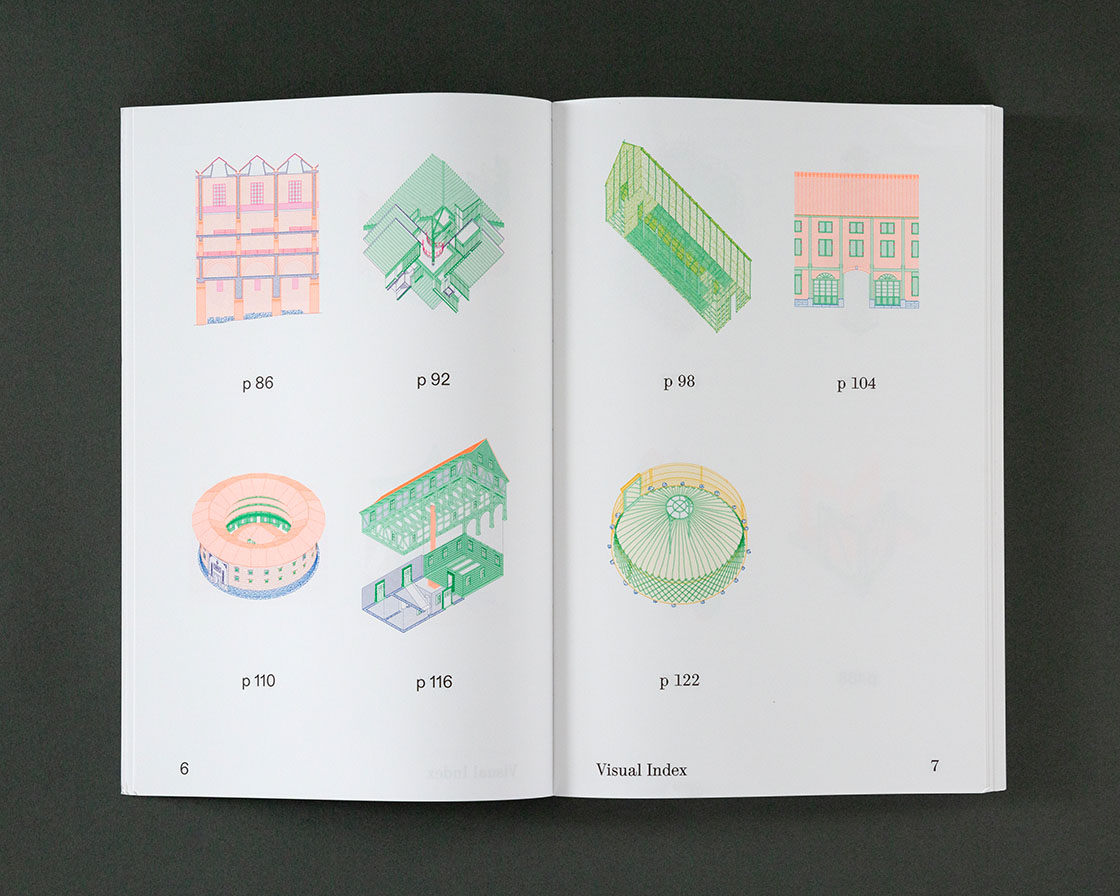

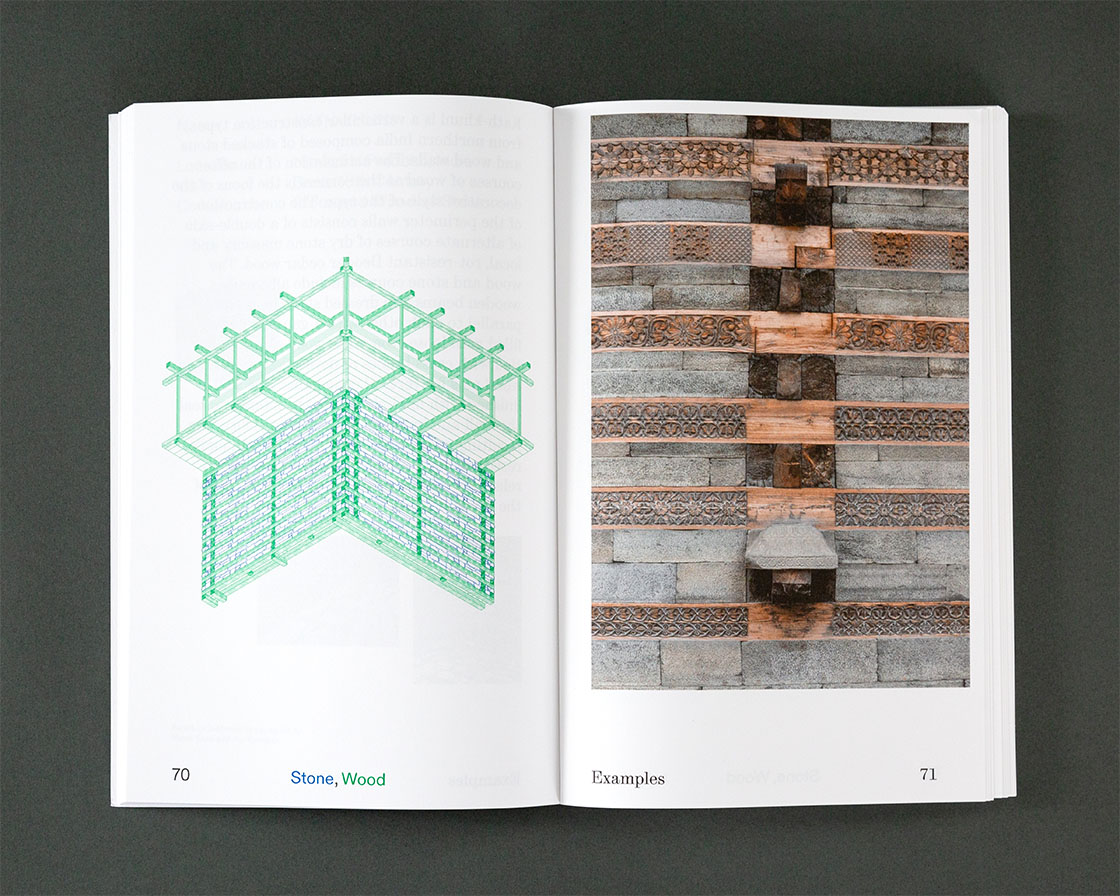

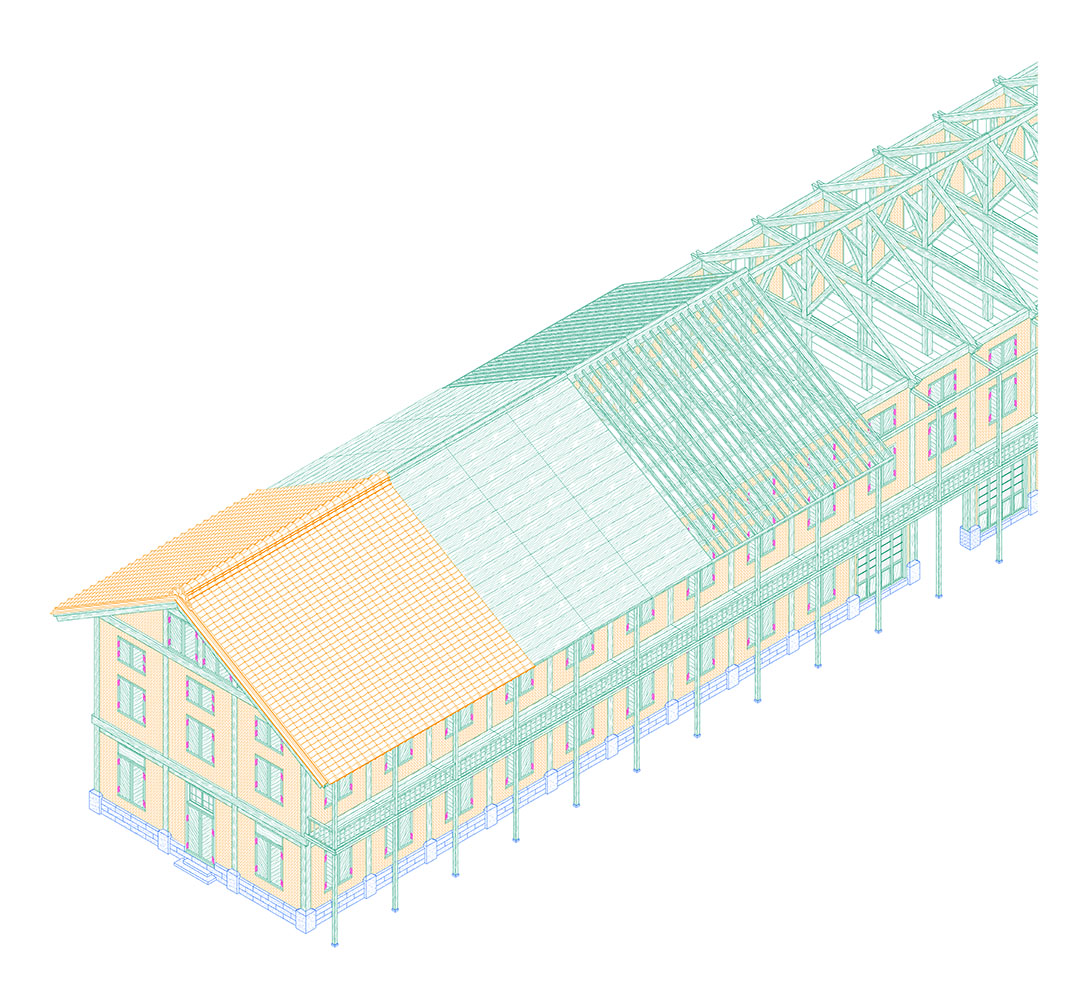

Divided into two distinct sets of research, the book advances an argument for the acceptance of an architecture, and architectural culture, that embraces heterogeneity, in the sense of both the use of mixed materials and radical inclusion. The first section comprises examples of buildings that exhibit properties of heterogeneity, drawn in color-coded detail and illustrated with photographs. These case studies, vernacular and authored buildings from across regions and time periods, are categorized by materials and construction types: collages, fills, sandwiches, scaffolds, stacks, and wraps.

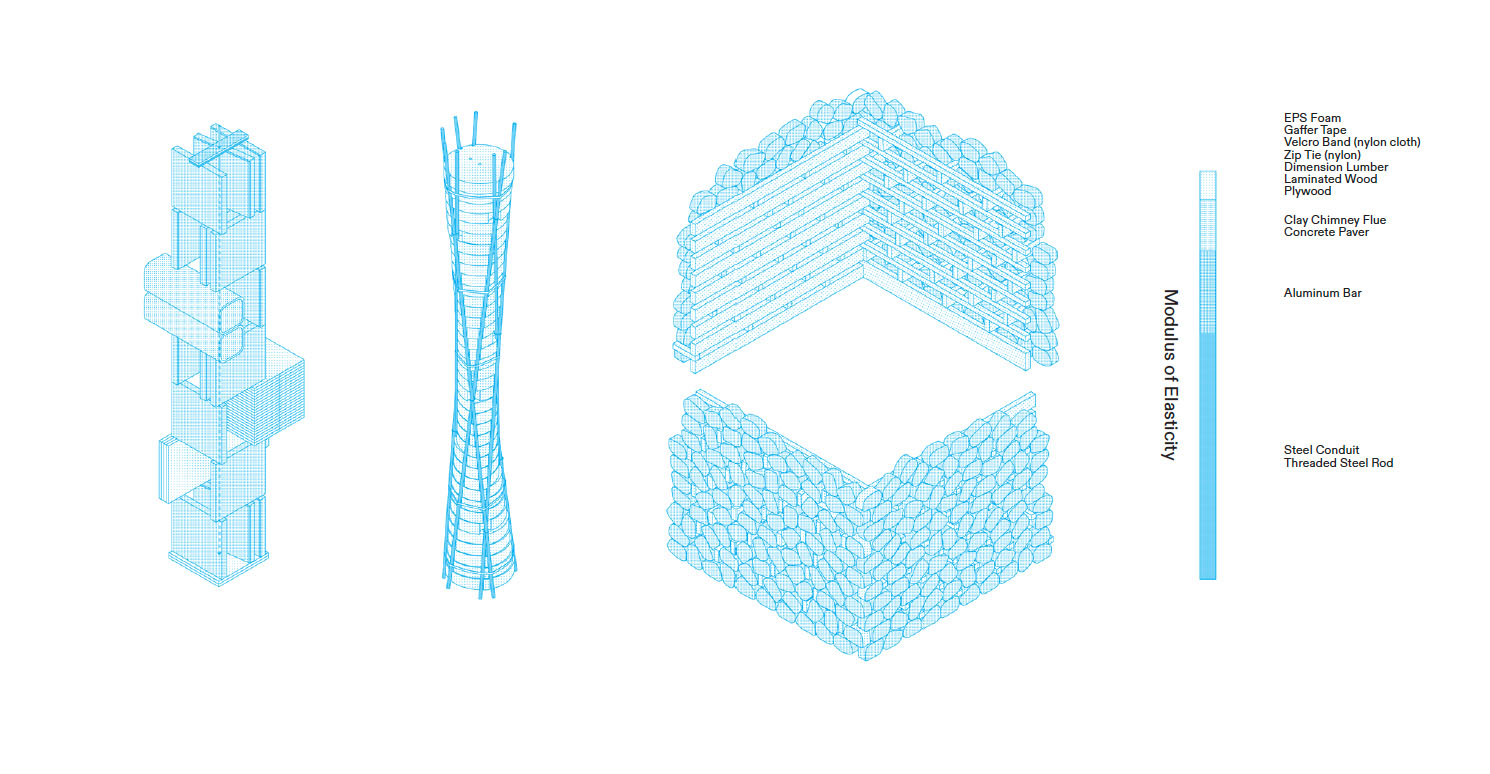

The second section is devoted to the documentation of a set of full-scale prototypes of building elements designed and constructed by students from UC Berkeley, Harvard Graduate School of Design, and Rhode Island School of Design. These forays into speculative architecture extrapolate on concepts derived from the case studies.

The research is complemented by essays contributed by Jesús Vassallo, Jeannette Kuo, and Ajay Manthripragada, assistant professor of architecture at Berkeley.

Forrest and Vobis are cofounders of the award-winning design firm Ultramoderne and have collaborated with Schneider, a structural engineer, on numerous projects, including Chicago Horizon. That project, the winning design in the 2015 Chicago Architecture Biennial Lakefront Kiosk Competition, used cross-laminated timber in a “quest to build the largest flat wood roof possible.”

Turan is a founding partner of the award-winning architectural office NEMESTUDIO. Her research and practice investigate the collision between architecture and climate change through the lenses of representation and materiality. Turan’s Hempo Longhouse, a code-compliant small house in California built with a panelized hempcrete assembly system, aims to accelerate the widespread adoption of this promising low-carbon biomaterial.

Neyran Turan: I want to start with your book’s topic, heterogeneous construction, and its potential. On the one hand, the book situates itself amid current discussions around decarbonization and argues to go beyond the hyperspecialization of building parts. On the other hand, the book is a call against purity and embraces hybridity and imperfection as an aesthetic sensibility.

This is an interesting aspect of the book, which understands architecture as an active negotiation between cultural and aesthetic concerns. Can you talk about this double take?

Yasmin Vobis: The hope was that we could try to get at this topic in many different ways. I think it might be helpful to talk a little bit about where this project came from. The three of us had been working on projects in mass timber, and in particular, Chicago Horizon, at a moment when mass timber was seen as the answer to everything, and when design aesthetics dictated that everything had to be just one material.

We felt that there were some serious drawbacks to that way of thinking, where everything has to be so relentlessly pure. When we worked on a larger scale project, for example, we realized that we needed other materials to take on the roles that mass timber couldn’t. But aside from these practical implications, aesthetic possibilities also emerged. I think that there’s such richness and architectural potential for references when we start to think about mixing materials.

Aaron Forrest: When we started this research, it was in the context of coming out of these mass timber projects, like Yasmin said, but also we had just started to take an interest in more global construction cultures, looking in places like Northern India and parts of Africa and East Asia.

The Kath-Khuni architecture in northern India is one example of an architecture that combines wood and stone. We admired the inventiveness of people who were designing and building only with what was available within a few miles and it really drove us toward resourcefulness and inventiveness in our own work.

Our own context is a little different. Being in a highly industrialized North American economy, our context is Home Depot and Lowe’s, but it seemed like we could learn from these examples — how could we employ a similar resourcefulness? So we began working with cheap and easily available materials, but also materials that might have been discarded or needed to be reused from other construction projects.

The other thing that your question sparked to my mind, Neyran, is this idea of the architect or designer as a negotiator among many different competing conditions. I think that’s definitely true. But I think for me and Yasmin and Brett, having collaborated on built works, I hesitate to use the word negotiation, because it makes it sound like we’re all on different sides of the table. I think that our approach has been, both in design work and in this more scholarly realm, more conversational, more dialogue-driven.

Brett Schneider: It speaks to some of the assumptions we have in the design disciplines about collaboration, that we’re each coming from separate positions. But this book, and a lot of the work we’ve done design-wise, has not been that: we overlap. And, in a way, the nature of the project is very similar to the outcome of the book, in that we’re working in overlaps — we’re working in heterogeneous conditions. So this ties into this question of the book being about the culture of design, not just about construction.

NT: There seems to be a heterogeneity in your way of working. But I still want us to talk about negotiation. I was really struck by Brett’s essay on regulatory systems and building codes in relation to heterogeneity in construction. Brett writes about technical regimes like residential building codes that are related to, for instance, biomaterials and the difficulties in that domain. I am familiar with this aspect through my recent work on hempcrete construction. Do you think there’s a role for us as architects to expand these discussions in relation to the building codes of low-carbon biomaterials?

BS: Building codes were developing in the 20th century at the same time there was a consolidation to industrial materials and this was tied to a concurrent development of the theory of plasticity that became embedded in the structural requirements of these codes. The result was that materials and assemblies that were outside this performative paradigm fell out of acceptance.

One counter to this consolidation is some of the work of Jacques Heyman at Cambridge that describes the performance of stone structures within an expanded definition of plasticity through the adjusting geometry of the assembly rather than in the material itself. In addition, several of the stone and wood assemblies we’ve highlighted in this project, like Kath-Khuni and Goz Dolma, have been identified as having a plasticity as a system rather than materially. These cases imply that the structural requirement of plasticity need not be so exclusionary and that the inclusive spirit of this project can extend to questions of performance. The challenge then is one pushing against the orthodoxy of the regulatory bureaucracy and this will take time.

If the imperative is to expand the palette of materials to include those that are more sustainable, then this process may be too slow. This implies an additional heterogeneity in that the push for acceptance must come in multiple ways — expanding paradigms, but also finding combinations of currently acceptable practices like Roger Boltshauser’s use of post-tensioning for earth construction. All of these examples are about changing the framing of how we think about materials in combination rather than as singular.

AF: When Yasmin and I were in school, there was a lot of discussion around drawing being the medium of architects: that architects produce drawings, and then other people take those drawings and use them to produce buildings. And I think that always rubbed us the wrong way. We were always interested in getting our hands dirty, but not to the degree where we think everything should be design-build, but that there might be a fruitful interplay between the process of design and process of construction, that you could treat that whole entire process as a continuum.

Looking at some of the examples from the 20th century, in particular, you see architects not only designing amazing buildings, but also doing a lot of the testing and mock-ups in order to demonstrate that they could be viable. Félix Candela is a great example.

Now that there’s a lot more interest in what you, Neyran, called bioregional materials — which have great benefits in terms of sustainability but also present problems in terms of predictability and permitting — there might be an opportunity for architects to dive back in to the question of how we involve ourselves in the construction process. Can we see that as part of the experimentation, or the design process, in order to drive things forward?

NT: That leads nicely to the book’s section on physical prototypes, which are somewhere between a mockup and a 1:1 scale model. It might be interesting to discuss them both in terms of their role in the book and as a pedagogical method in your teaching. One thing about these prototypes is that they almost reintroduce a different abstraction. In the book, you talk about sleek appearances or concealing, and usually, that’s how the word abstraction is understood in architecture — as something more aligned with perfection. But your prototypes provoke another kind of abstraction that embraces imperfection. By deleting certain layers, they are deliberately acting as conceptual models.

YV: Neyran, that’s so beautifully put. I think we initially saw the prototypes as a way to think about how we could take some of these lessons from the vernacular examples, and bring them into our contemporary design context.

I like the way that you’re positioning them as models, as being both abstract but also very real and specific. Because I think they are in this weird space, in the sense that they are almost like diagrams of structures. They have a kind of structural logic, a diagram embedded in each one of them, and they’re performative in the sense that they are building elements, but they’re not actually in buildings. They’re columns, but they’re not actually loaded columns. They’re walls, but not actually loaded walls. So in that sense, they’re abstracted models of a condition, and at the same time they have a specificity as architectural objects, because we’re using the real materials.

NT: In line with the conventions of architectural representation, models being one, maybe we can talk about the drawings in the book. What are the limits of the representational in our discipline, in terms of heterogeneity?

AF: We’re all heavily invested in drawing and the representational culture of architecture — I think that is demonstrated in the effort that went into the drawings in the book — but the usefulness of the drawing does break down at a certain point. If you’re trying to understand the way that a piece of stone and a piece of wood relate to each other, at some point you need to see those things as physical objects in front of you, and put them one on top of the other, and see what happens.

And so even though I think we approached the prototypes as a design exercise, and that there is a virtuality to that, as Yasmin noted, at the same time we’re trying to see how things work, how they actually fit together, how they put forces onto each other — it’s something that a drawing just cannot do. And so you have to understand the virtuality of the drawing and the reality of building materials in dialogue with each other. And I think that’s what we tried to do, working through multiple media in the book.

NT: How do you think this research has impacted your teaching?

BS: I know that my teaching has radically changed in the last four years because of this work. I’m now much more conscious about looking at broader overlaps between the largely technical subjects I teach and other areas, be they historical, be they theoretical, be they design based — how does an expanded palette of materials get incorporated, how does the vernacular translate into a different context? As an engineer, the questions become less mathematical and more generally logical about how things work. And I’ve been really energized by it.

In that sense, heterogeneity is also a model for our disciplines: there are distinct layers of specialization but somehow there needs to be a generalist attitude that is more about our commonality than our differences. How can we see and embrace the heterogeneity that already exists in the world? I love Aaron’s line at the end of the introduction [reads]: “The heterogeneous might instead be understood as a deep and broad body of knowledge that demands to be read, interrogated, and constantly reworked.”

This is the lesson I pound into my students now: you know that all of the things you design are compromised and imperfect. When you embrace that, then the process becomes one of designing that imperfection and that means that everything can be reworked and I think that’s freeing.

YV: For me, like Brett, the research has had a huge impact on my teaching. I teach an introductory course on construction, and that is a class that students sometimes approach wanting to have a certain set of answers about how you do things in contemporary construction. And I think this research has upended so many of our assumptions about the way that we typically do things.

One thing I try to think about now with my students is, how do you impart a sense of curiosity and also experimentation with construction? The technologies that they’re studying today won’t necessarily be the same technologies they’ll be working with in 10 years when they’re out in the field, because things are changing so quickly, so having an openness and a sense of experimentation is essential.

BS: When we talk about sustainable materials, these are often assemblies that don’t have a defined appearance associated with them, right? So we can say to our students: This is an opportunity to make an architecture that’s different from anything that’s come before.