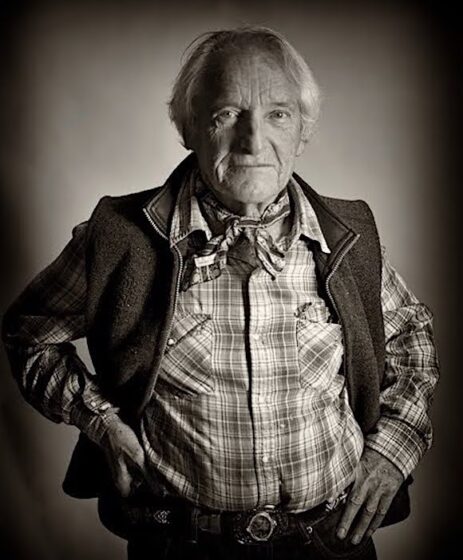

Sim Van der Ryn, pioneer of ecological design, passes away at 89

The College of Environmental Design mourns the loss of Sim Van der Ryn, professor emeritus of architecture. A designer, teacher, writer, and artist, Van der Ryn passed away on October 19 at the age of 89.

Van der Ryn, often called “the father of green architecture,” is renowned as a pioneer of sustainable design, although he preferred the term ecological design. He aimed to create buildings and communities that were sensitive not only to place, but to the flow of human life. “A building should tell a story / About people and place / And be a pathway to understanding / Ourselves within nature,” he wrote.

“Sim Van der Ryn was a visionary,” says UC Berkeley Professor of Architecture Greg Castillo, an architectural historian and expert in the 1960s counterculture. “He was working in sustainability at a time when the architectural profession was turning toward postmodern formalism. But now the world has caught up — and we are seeing a new wave of scholarly interest in his work.”

Van der Ryn taught architecture at Berkeley from 1961 to 1995, with a four-year hiatus in the 1970s to serve as California State Architect. He was a founder of the Farallones Rural Center, a nonprofit dedicated to sustainable and renewable technologies, and a practicing architect. At Berkeley’s College of Environmental Design, he influenced generations of architects to think critically about the social and environmental impacts of their work.

“Sim was one of the people who laid the foundation for CED’s ongoing commitment to resilience and environmental equity,” says William W. Wurster Dean Renee Y. Chow. “He was focused on how to build in environmentally friendly, energy-efficient, socially just ways long before ‘sustainability’ was even a term in the architectural lexicon. His influence, on Berkeley and beyond, is profound.”

Becoming an iconoclastic architect

Born into a Jewish family in The Netherlands in 1935, Van der Ryn fled with his parents and siblings to New York, arriving in 1939. As a child, he found peace and a sense of security in the weeds and puddles of empty building lots and along railroad tracks. “I was happiest outdoors,” he wrote in his 2005 book Design for Life: The Architecture of Sim Van der Ryn.

He studied architecture at the University of Michigan but chafed under the Modernist orthodoxy of his Mies van der Rohe–trained professors. Instead, he found inspiration in the maverick philosophy and architectural innovations of Buckminster Fuller. “He unlocked for me the connection between nature and technology,” Van der Ryn wrote. Fuller’s ideas led Van der Ryn to believe that good design, approached as a comprehensive whole, could be a tool to solve the world’s problems.

Van der Ryn also eschewed the conformity of East Coast architectural practice, turning down a job at SOM in New York to head West. He was drawn, he wrote, by the region’s “open spaces, wild nature, and spirit of adventure.” Northern California — especially at the dawn of the 1960s — turned out to be the perfect fit for the iconoclastic young architect.

Forging an ecological approach to architecture

In Berkeley he found the freedom to experiment with new approaches to architecture that connected design to people’s lives and to nature. He rejected architectural high modernism and, against the backdrop of the Free Speech Movement, standardization, suburbanization, and the entire postwar rational-industrial society.

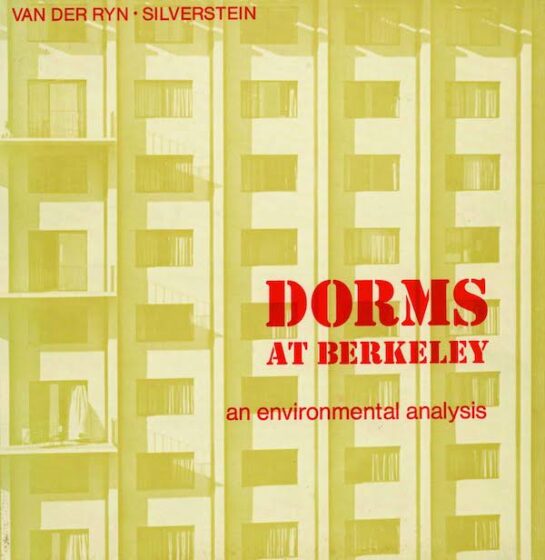

Van der Ryn’s humanistic outlook drove him to think about buildings as living systems, or ecologies, that included their users. His 1967 book (co-authored with Murray Silverstein) critiquing Berkeley’s new high-rise residence halls was based on observations and interviews with students. This was an early work in the field of post-occupancy evaluation, which was emerging as an important area of research at Berkeley under professors Clare Cooper Marcus, Russ Ellis, Roselin Lyndheim, and others.

At the end of the 1960s, Van der Ryn moved his family from Berkeley to a forested ridge in Inverness, California, where he built his own house in the woods. He was searching for ways to embed his life and architecture within the cycles and flow of the natural landscape.

During the 1971–1972 academic year, he and Jim Campe, a lecturer in the Department of Architecture, led a design/build studio in Inverness. “I wanted to teach what I was just learning to do: making a place in the country,” Van der Ryn wrote in a contribution to a volume commemorating the 100th anniversary of Berkeley’s Department of Architecture.

Fifteen students, many of whom had never before wielded a hammer or saw, constructed communal buildings and their own living pods on Van der Ryn’s land using salvaged, repurposed materials. “For everyone, including myself, it was a powerful life-changing experience,” he recalled.

Teaching sustainable design practices at Berkeley

Back in Berkeley, Van der Ryn continued this vein of hands-on studio teaching with the unsanctioned construction on campus of a fully sustainable building core, dubbed The Energy Pavilion (1973). The structure, erected outside Wurster Hall, brought together all of the energy-saving technologies then known and showed how they could work together. That experiment led to the Integral Urban House, a collective project with Van der Ryn’s Farallones co-founders Bill and Helga Olkowsi that grew out of a 1974 studio at CED.

The Integral Urban House demonstrated the possibility of creating a self-sufficient, eco-friendly home in the city. The renovated Victorian in West Berkeley incorporated recycled materials, a gray water recycling system, a solar water heater and solar oven, a waterless toilet, and a composting system, as well as a vegetable garden, chicken coop, and beehives. The house was open for public tours and hosted community programs to teach sustainable living practices.

“Sim was ahead of his time in trying to mainstream what were then counter-cultural concerns about the destruction of the environment,” says Castillo. “When the Energy Pavilion was built, it was before the oil crises of the 1970s. But Sim was already thinking past that, understanding that extractive fossil fuel technologies were doing irreparable environmental damage.”

Bringing sustainable design to Sacramento

Van der Ryn brought this environmental lens to his work as California State Architect during Jerry Brown’s first term as governor. In the context of the 1970s energy crisis, Van der Ryn and his team designed energy-efficient government buildings, such as the Gregory Bateson Building in Sacramento (1981). Featuring passive solar design and natural ventilation, it was the first large-scale building in the United States designed specifically to save energy.

During his time in Sacramento, Van der Ryn launched the Office of Appropriate Technology to promote renewable energy and reduce administrative barriers to small-scale, self-reliant, sustainable projects. Until it was shut down in 1983 by Governor Deukmejian, OAT sought to inject sustainability practices into state government agencies and educate Californians about solar panels, composting, drought-tolerant gardens, and other environmentally friendly ways of living that are de rigueur today. Van der Ryn also organized a bicycle sharing program for the State Architect’s office, presaging current urban bike-sharing initiatives.

From sustainability to resilience

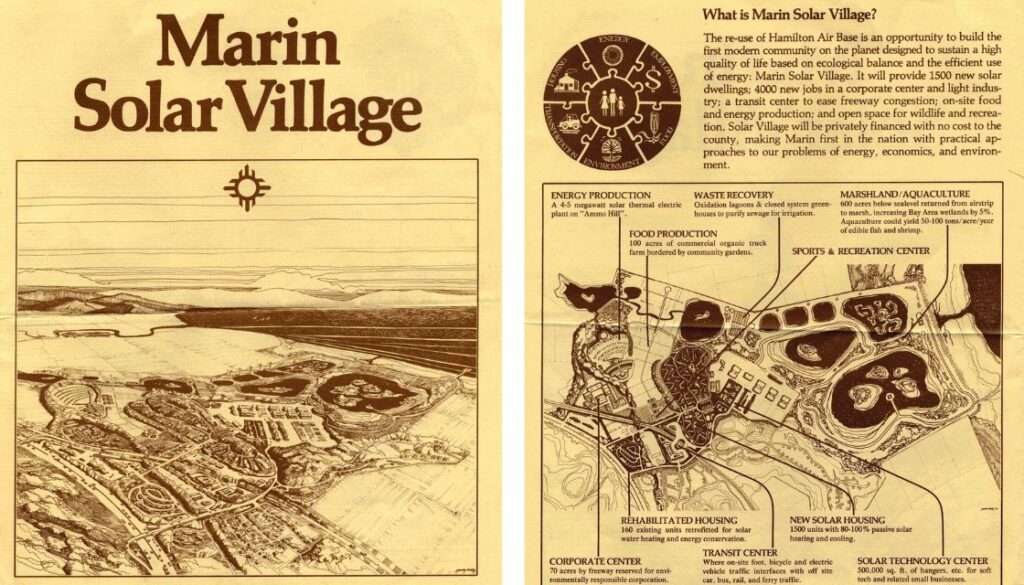

Environmental sustainability was central to Van der Ryn’s private architectural practice as well, which included residences, commercial and civic structures, educational institutions, health and wellness centers, and mixed-use residential communities. He experimented with energy-saving construction techniques like rammed earth, straw bales, and green roofs, and he designed the Marin Solar Village, an energy-efficient housing development planned for Hamilton Air Force base that unfortunately never came to fruition.

Van der Ryn published numerous books, including Ecological Design, with Stuart Cohen; Sustainable Communities, with Peter Calthorpe; and Design for an Empathetic World that spread his ecological and humanistic approach beyond California. He received many honors over the course of his career, including fellowships from the Guggenheim Foundation, Graham Foundation, Rockefeller Foundation, and Institute of Green Professionals, as well as a lifetime achievement award from the Congress for New Urbanism.

Later in life, just as he was being recognized as the father of green, or sustainable, architecture, he began to move beyond those terms. In a 2008 speech, he said, “What we need to create are resilient communities, resiliency at every scale. To me it is more than just cities. Resiliency has to include the basic elements — it’s soil, it’s water, it’s energy, it’s land, buildings, communities, and a social structure . . . . Sustainability is a static concept. Resiliency is dynamic.”