Redefining the limits of urban design, MUD studio takes to the Salinas Valley

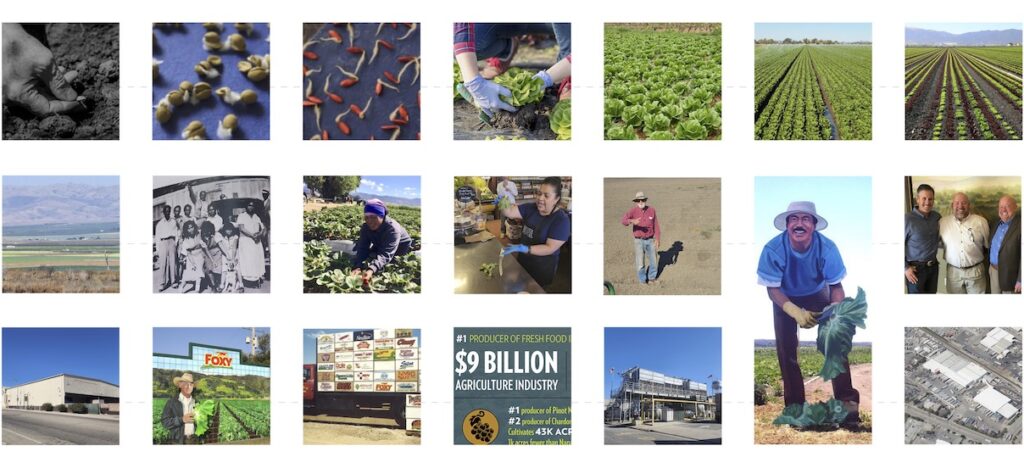

Urban does not begin and end in cities. Particularly in California, the birthplace of modern agribusiness, agriculture provided the capital and infrastructure for urban expansion. The Salinas Valley — one of the richest agricultural regions in the world — encapsulates the state’s cultural, environmental, and economic histories. And yet, “most people driving on Highway 101 through the valley do not stop; there’s hardly even a farm stand,” says Margaret Crawford, director of the Master of Urban Design (MUD) program at the College of Environmental Design (CED).

To address this disconnect, Crawford teamed up with instructor Ettore Santi, a PhD candidate in architecture at CED, and Scott Elder, a lecturer in MUD who has been working with the National Park Service on the valley’s Anza Trail, to design the fall 2022 MUD Advanced Studio course focused on the Salinas Valley. Their goal was to create opportunities for students not only to think deeply about issues in California urbanism but to take them on by working with partners in local communities.

This course is one example of MUD’s aim to redefine the limits of urban design by looking at all kinds of landscapes. “It’s one of the rare classes that focuses on an agricultural area,” says Crawford. She points out that investigating the long-ignored environmental, water, and food systems of rural California lifts the curtain on the assets, needs, and opportunities of the state’s agricultural regions.

Community Partnership

The 15 students in the studio began the semester with a five-day research trip through the Salinas Valley. Their first stop was to meet their community sponsor, Craig Kaufman of the Salinas Valley Tourism & Visitors Bureau. He told them how the NGO has tried to raise awareness of the region in order to increase tourism — and thus revenue for the area’s much-needed social services. MUD students then traveled throughout the valley to meet with local stakeholders and decision-makers, including staff at the Farm Bureau, the John Steinbeck Center, and the National Park Service, as well as farmers and historians of Indigenous history. These were the locals the students would partner with as they developed projects highlighting what makes the Salinas Valley special.

The six resulting projects, developed through the lens of low-impact tourism, address issues such as equitable economic development, environmental restoration, public space activation, housing, community cohesion, and the use of education to engage people with the valley.

Students were also tasked with creating visual presentations for their partner-stakeholders that were accessible — reinforcing the idea that community partnership is central to urban design. “From the beginning, I asked students to think of their design visuals as public images and not just images for design experts,” says Santi. “They got creative and tried to be realistic, making presentations that would be comprehensible for people in the community.”

“It took a little deprogramming to realize that if I really wanted people to look at my drawings, I needed to make them legible,” says Isha Khan, a student in the studio. She started drawing in full color, with a collage approach that was granular but rich. “Bringing life into the drawings was new for me.”

Projects

Travels with Steinbeck

Travels with Steinbeck, by Khan and Patricia Flores, proposes a strategy of literary tourism, establishing trails that connect sites mentioned in Steinbeck novels set in the valley. They were inspired by the ways that Steinbeck rendered the lives of valley residents, particularly farmworkers, in relation to the landscape. The trail, punctuated with experiential anchors, serves to revitalize urban spaces, including an underutilized parking lot in the center of Salinas.

Khan and Flores’s project transforms this space into Civic Commons, a marketplace where local people could sell goods and access legal and healthcare services. Travels with Steinbeck also includes the establishment of campgrounds to experience the night sky without light pollution. “The trails allow people to experience the smell, sounds, and tastes and be involved with the landscape and the culture,” says Flores. “We took advantage of the landscape already there to give it back to the community, and worked to make sure that the tax revenue would benefit people who need it.”

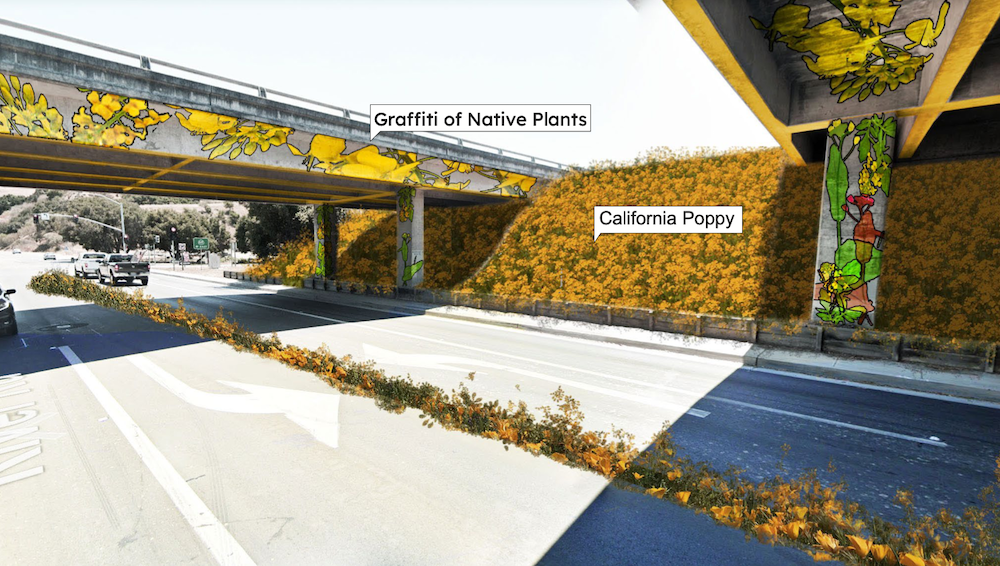

Anza Trail

Juaxing Cui, Sen Du, and Xuyuan Fan focused on the historic Anza Trail, which marks the route that Spanish commander Juan Bautista de Anza established in 1775–1776 to extend Spain’s colonial territory into the Bay Area and which is largely invisible today. Referencing the ways the valley entwines Indigenous, colonial, and cultural threads of California’s history, their plan revives the precolonial landscape, marking the Anza Trail with native wildflowers as it winds through reconceived landscapes, California missions, and other historic sites. It proposes two land restitution strategies for sites important to the Esselen Tribe of Monterey County and incorporates open-air museums, food stops, and craft markets into the missions located along the trail. The path also leads through wineries, creating opportunities for glamping sites and outdoor activities.

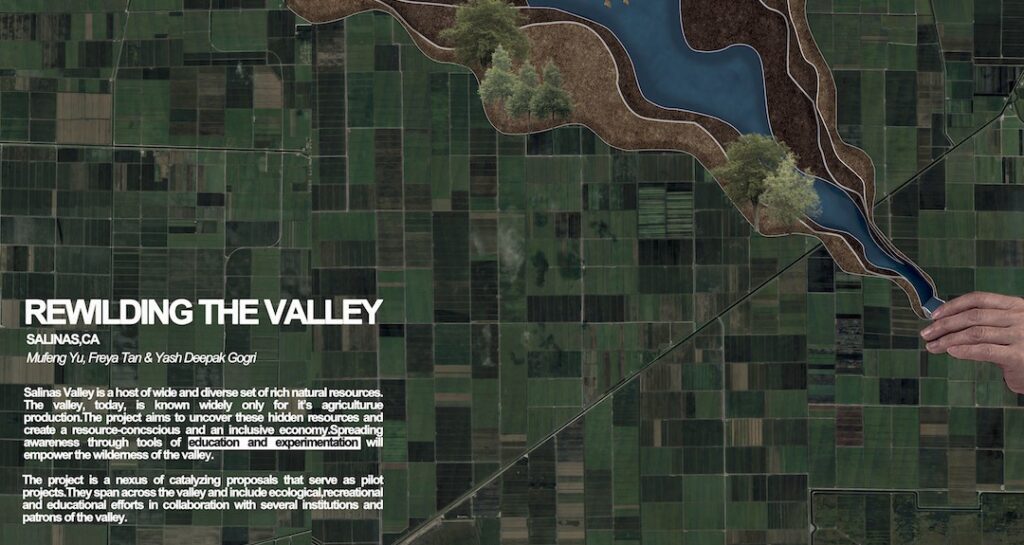

Rewilding the Valley

For their project, Rewilding the Valley, Mufeng Yu, Freya Tan, and Yash Deepak Gorgi analyzed how agribusiness operations have transformed the diverse ecosystems of the valley. They designed a network of catalyzing pilots to revive ecology, promote knowledge, and highlight and redistribute natural resources to bring in tourist activities. “We’re trying to shift the identity of the Salinas Valley to become a model of agriculture: economically diverse, ecologically sustainable, and breeding innovation at the intersection of ecology and technology,” says Gorgi. The plan incorporates six interventions, including regenerating the estuary where the Salinas River meets Monterey Bay to revitalize lost biodiversity and transforming a flood inundation zone in Salinas into a biodiversity park for demonstrating different farming techniques.

Agroway

The Agroway project brings to light the massive but largely out-of-site agricultural processing that occurs in the valley. For their proposal, Rita Ling, Yaoyao Ding, and Byron Li added nodes along Highway 101 to encourage people to stop and get out of their cars to engage with what is being grown in the valley, as well as the growers. Their project creates opportunities for farm and ranch visits and greenhouse workshops, as well as proposes a food hub similar to the Eataly concept but focused on the Salinas Valley. The hub integrates a grocery store, restaurants, and kitchens, as well as demonstration farms that allow interaction with the production line.

Housing the Valley

Equitable economic development was a theme throughout the course. Students Sagarika Nambiar, Srusti Shah, and Varun Shah considered how tax revenue from their project could support needs like housing and social support for a largely migrant workforce. The Housing the Valley project looked at the economic, ecological, and land-use changes that have allowed the valley, with its scarcity of housing, to become “the salad bowl of the world.” Leveraging the cyclic nature of activities in the valley, the students developed site-specific, flexible, low-cost housing solutions with different degrees of permanence. They proposed linking the development of a range of housing typologies with a land banking system to produce financial strategies that would help create multiple housing options for workers.

Images of the Bowl: An Infrastructure of Images for the Salad Bowl of the World

Images of the Bowl: An Infrastructure of Images for the Salad Bowl of the World is a billboard-based project. Student Diego Gonzales collected and examined images of vernacular buildings, lettuce landscapes, agribusiness graphics, and Mexican textile arts in the valley to distill the locale’s visual language. He then created a set of billboards, mural paintings, and public images visualizing the complex history and identity of the “salad bowl of the world.” The main piece of the project is an observation tower from which visitors can see the iconic valley landscape from a new perspective. The tower also serves as a food stand and “gateway” billboard signaling access to the Salinas Valley.

Crawford and Santi agree that the studio was a success. “These projects would be great if they were implemented,” says Crawford, who is in talks with the partners in the valley about continuing MUD’s involvement there. “The positive response from the community testifies to how impactful the work was.”

“The fact that the students were willing to give up their big abstract ideas and make their projects real was a moment of growth, of developing their abilities as designers, as professionals,” says Santi. “Because that’s what being an urban designer is about — getting real.”