Liz Gálvez joins the Department of Architecture

The prize–winning architect, whose work centers around developing new environmentalisms in architecture, is interested in integrating energy and material processes with design to develop new ways of living.

The research of Liz Gálvez, the founding principal of Office e.g. who joins the Department of Architecture as assistant professor this fall, couldn’t be more timely. As temperatures in Phoenix smashed all records in July — 31 consecutive days at 110 degrees or above — Gálvez was gearing up for a grant-funded investigation of heat risk mitigation in desert cities, with Phoenix as the primary case study.

A registered architect who has taught at the Yale School of Architecture, Rice School of Architecture, and University of Michigan’s Taubman College, Gálvez is interested in the interface between architecture, theory, and environmentalism through a re-examination of building technologies. Her work is centered around reimagining how we will live, and not only subsist, in the future.

“I am interested in how buildings work. I want to get students excited about building systems and their invisible processes,” she says, citing as an example architectural strategies for passive heating and cooling. With the advent of building technologies such as air conditioning, she explains, the responsibility of determining how to make and condition our buildings has slowly shifted away from architects. “I believe that to address the current climate and environmental crisis architects must work to re-engage the reciprocities between material and immaterial matters of concern through the matters of architecture: aesthetics, form, and space-making.”

Gálvez, who is Mexican American, is also interested in the processes behind the scenes of the architecture profession. With designer and researcher José Ibarra, an assistant professor at CU Denver, she received a 2023 Graham Foundation grant to organize a symposium for Latinx designers to come together. They aim to define a more recognizable community of Latinx scholars that can support current and future generations of Latinx architects. As increasing numbers of Latinx students enter architectural education, Gálvez and Ibarra understand the value of encountering faces similar to one’s own during the educational journey.

Berkeley, with its tradition of progressive activism and environmentalism, attracted Gálvez from the East Coast. “I’m excited to be in Berkeley, a place where people have long thought about the repercussions of how we live in the world,” says Gálvez. “Attempting to live with an environmental conscience is a way of life in the Bay Area.”

Things that matter aren’t necessarily visible

Gálvez’s recent projects elevate environmental processes as an aesthetic practice in relationship with form to investigate the invisible properties of architecture. “In the context of climate change, things that matter, for example energy dependent processes like air movement and comfort, aren’t necessarily visible,” she says.

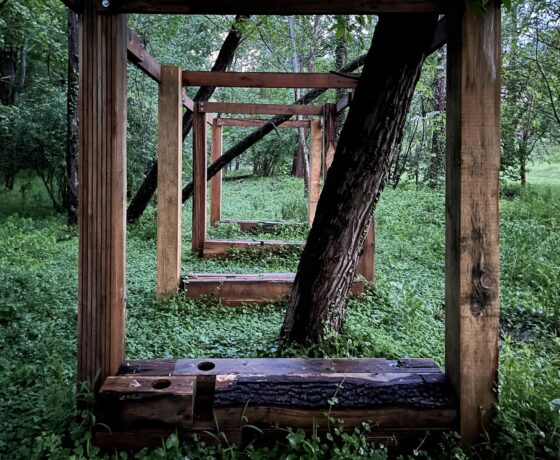

From Wood to Tree (2022), an open-air pavilion Gálvez designed for the University of Virginia campus, investigates both the production of wood and its reciprocal process toward biological degradation as a design methodology. Gálvez used fabrication tooling to texture and puncture the structure’s lumber to encourage its colonization by saplings, insects, and fungi, engaging the cycle of transforming the processed wood back into a tree rising from the forest floor.

The gallery installation Of Envelopes & Air (2021) reconsiders the building envelope as a permeable membrane. It brings Gálvez’s exploration of process together with her interests in mechanical systems and the unseen aspects of building performance through environmental aesthetics. The primary material for the installation is air itself, as it passes through walls in various ways, transgressing the rigid separation between a civilized, conditioned interior and an uncontrolled, vast exterior.

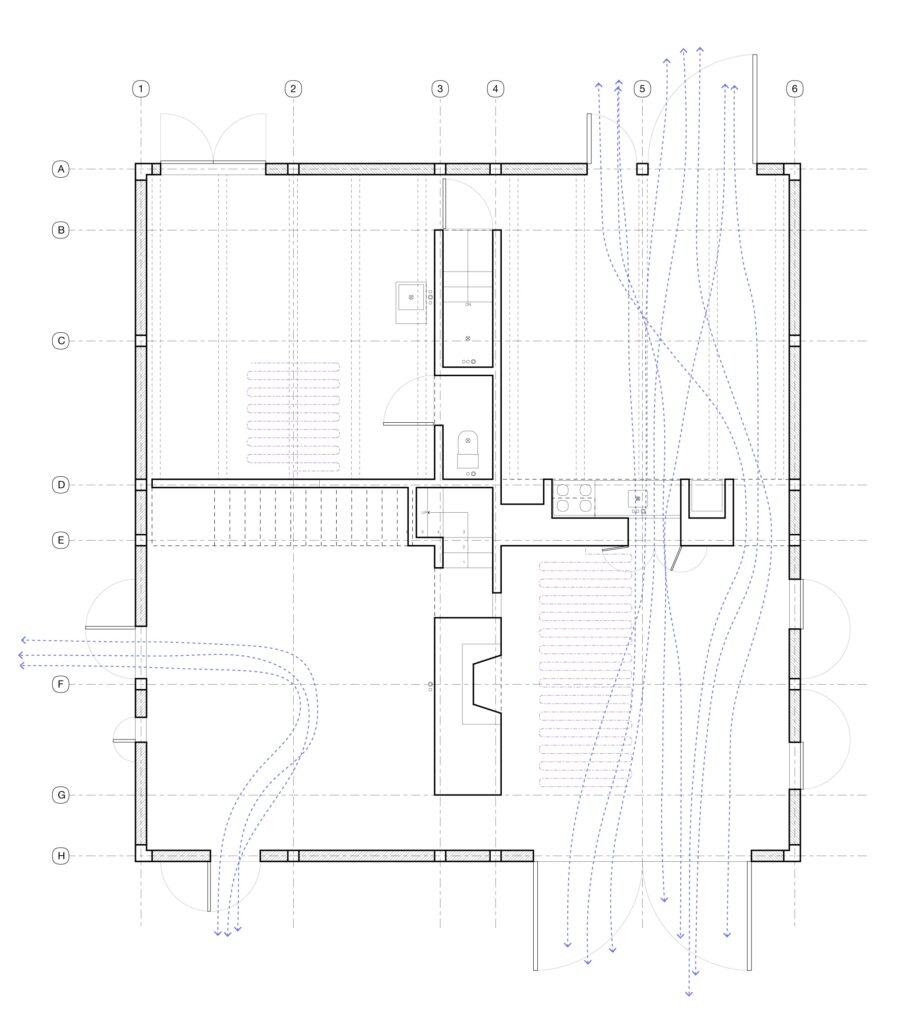

For a house about to break ground in Michoacán, Mexico, Gálvez translates the possibilities of this permeable architecture into a built project. Designed for both passive heating and cooling, the house is anchored by a central masonry hearth. While efficient in cold seasons, the cruciform hearth could block the free flow of air in warmer weather; Gálvez solves this problem by making apertures in the hearth to allow cross ventilation and using fenestration to elide the boundaries between exteriority and interiority.

“I’m interested in stretching the bounds of indoor comfort, not only practically but aesthetically, psychologically, and culturally. These ideas also inform the Phoenix-based research project,” says Gálvez.

Collective comfort: Radical ideas for resilience

Gálvez’s research/teaching project Collective Comfort: Framing the Cooling Center as a Resiliency and Educational Hub for Communities in Desert Cities, developed with Dalia Munenzon, an assistant professor at the University of Houston’s Gerald D. Hines College of Architecture & Design, is funded by a prestigious Research Prize from the SOM Foundation. It aims to address both the urgent need to provide immediate heat relief for Phoenix residents, especially low-income city-dwellers who are the most impacted by extreme temperatures, and the longer-term imperative to envision new forms of resilient architecture through collective action.

Gálvez and Munenzon are bringing community stakeholders together with partners in resilience planning, engineering, and architecture to collaborate with Berkeley MArch students on the development of Collective Comfort over the course of the 2023–2024 academic year.

The project proposes a new vision for cooling centers that teach visitors about sustainable ways to adapt their homes in the face of the invisible danger of extreme heat. By bringing this education to the forefront, and providing alternative models, Gálvez and Munenzon hope to destabilize the fossil-fuel reliant single-family home.

They also plan to develop heat-resilient prototypes for multiple building types, from ground-up cooling center structures to existing church buildings. They are collaborating with community organizations who will be able to use these designs in their applications for Federal grants that support hazard mitigation.

Gálvez says, “One approach is to be exposed to a wider range of idiosyncratic temperatures ‘inside’ buildings, in the same way that we embrace dynamic temperature differences outside. We may have to update our architecture in ways that are radical. And that makes this an exciting time to be an architect.”