Lester Wertheimer on studying architecture at Berkeley at midcentury — and why he supports the Stump Traveling Fellowship

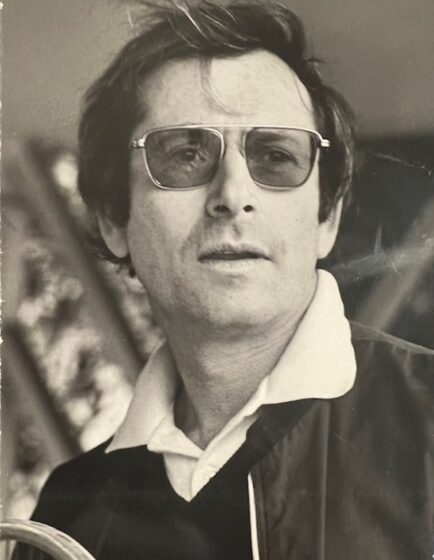

Architect, author, and educator Lester Wertheimer, FAIA, credits his success to his experience studying architecture at UC Berkeley in the 1940s and 1950s. “My life was because of Berkeley,” he exclaims.

Now 95, Wertheimer (BA Architecture 1951, MArch 1952) completed his latest project, a house in Beverly Glen, just a few years ago. In addition to having his own architectural practice in Los Angeles, he is the founder of Architectural License Seminars and the author of many study guides and books on architectural history and planning.

Recently, he sat down with the College of Environmental Design to talk about his memories of Berkeley and why he supports a travel fellowship for Master of Architecture students.

Wertheimer recounts that one of the instructors who had a profound impact on him was Erich Mendelsohn, known today for one of the canonical works of Expressionist-style architecture, the 1921 Einstein Tower in Potsdam, and for his pioneering use of glass in commercial architecture. Mendelsohn had fled Nazi Germany for Great Britain in 1933, eventually settling in San Francisco in 1941.

“Once a week, Mendelsohn would cross the bay to teach us at Berkeley,” Wertheimer recalls. He remembers that the myopic German architect would lean over student drawings to see them clearly, a cigarette hanging out of his mouth. “Cigarette ash was always dropping on the drawings – once, the paper caught fire! That wouldn’t happen today,” laughs Wertheimer.

He also remembers the day that Frank Lloyd Wright held court for five hours in the brick courtyard of the Ark, the old architecture school building (now North Gate Hall). Wright was in San Francisco working on 140 Maiden Lane. Years later, Wertheimer was commissioned to build the addition to that 1948 landmark, the only Wright-designed building in San Francisco.

“I had called him up and invited him to come to Berkeley and speak to us students,” recalls Wertheimer, “but he wanted a large speaking fee – $250, which was a lot of money then – and we only had a few dollars!” But then Mendelsohn invited Wright, who agreed to come free of charge when asked by the famous architect.

He fondly remembers Professor Harold Stump (BA Architecture 1926), “a swell guy, a real original,” who used to park his Model A Ford right in front of the architecture building. “He was brilliant and nice to everyone,” Wertheimer recalls.

It was at Stump’s urging that Wertheimer applied for a travel fellowship, the competitive, university-wide LeConte Memorial Fellowship. Many of Wertheimer’s classmates were a bit older, attending school on the GI bill, and had been posted in Europe during the war. But he had never been abroad.

Wertheimer won the fellowship, which enabled him to travel for 16 months after graduation, seeing firsthand architectural monuments across Europe, North Africa, and the Near East that he had studied at Berkeley. “I saw every cathedral in Europe,” he says.

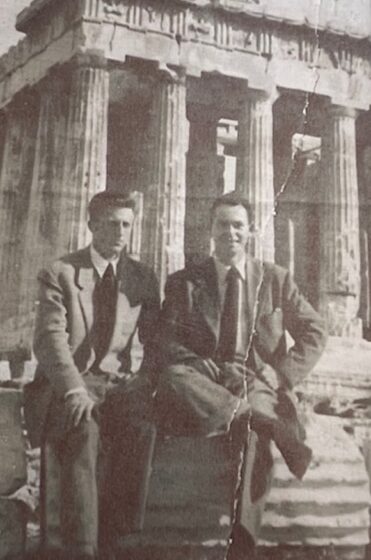

He made the Atlantic crossing by ship and on his first stop, London, ran into fellow Berkeley architecture student Beverley David Thorne (1924–2017). “Thorney and I traveled together for nine months and saw everything,” recalls Wertheimer. A photo of the pair atop the Athens acropolis captures them in the traveling clothes of the day: suits and ties.

One memorable experience they had was in Egypt. A guide led them to the top of one of the Great Pyramids of Giza, a steep and treacherous climb without any handholds. Once they reached the top, 40 stories high, it was too dark to descend. So, along with a handful of other tourists and guides similarly trapped, they spent the night on top of the pyramid.

“It doesn’t really come to a point like it looks in photos,” he explains. “There is about a 12-foot-square platform at the top. But it was quite an experience.”

While in Cairo, Wertheimer and Thorne looked up an Egyptian classmate from Berkeley, who turned out to live in a palace. “He drove us to Alexandria for lunch at a cafe overlooking the Mediterranean: I had never eaten on the sidewalk before. It was great, until a cat came by and stole the chicken right off my plate!”

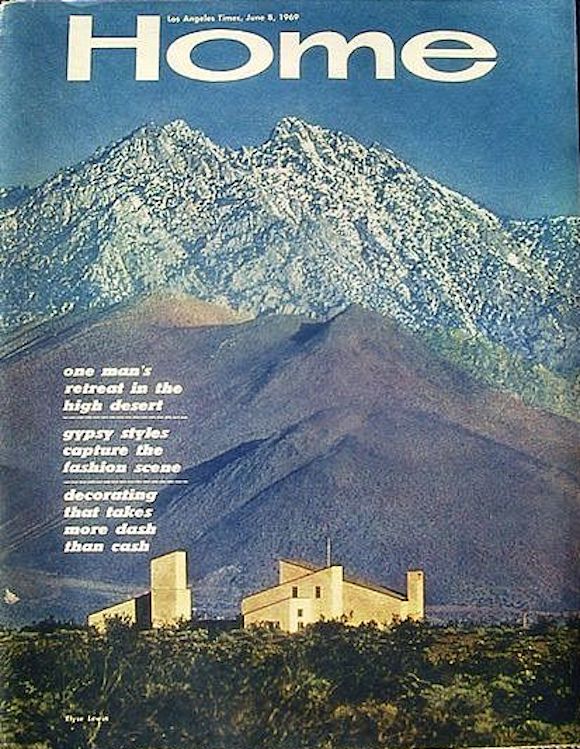

The opportunity to travel and discover the world’s great architecture profoundly impacted Wertheimer, as a person and as an architect. So in 2016, he and his wife Elyse Lewin, a photographer and commercials director, established the Harold Stump Memorial Traveling Fellowship, named for his beloved professor. It supports independent travel for MArch students to explore a particular architectural question or issue. The Wertheimers wanted to give future generations of Berkeley students the opportunity to explore world architecture as he had done in the early 1950s.

The Wertheimers love to hear about the travels of Stump Fellows, who present their research findings in an exhibition after their return. Recent recipients have traveled to southern Spain and Italy to study areas impacted by wildfires and to Brazil, Mexico, and Turkey to study housing typologies.

It makes Wertheimer reflect on his own odyssey: “Every day was a new adventure. It was a transformative experience.”