How CLT is changing the role of the architect

You may have heard of cross-laminated timber (CLT), the building material that’s gaining attention as a low-carbon, sustainable alternative to steel and concrete. But what you may not have considered is how CLT also has the potential to revolutionize the role of the architect.

“It’s bringing construction back into the architect’s realm, like the old master builders,” says Mark Anderson, a professor of architecture at Berkeley’s College of Environmental Design and principal of Anderson Anderson Architecture.

CLT, an engineered wood product created by layering and bonding smaller pieces of lumber together at right angles, is just emerging as a building material in the U.S., although it has been popular in Europe for decades. CLT can be manufactured from small trees that need to be cleared from forests to prevent wildfires, from large trees that have already burned, or from farmed trees.

In addition to actively sequestering carbon, CLT (also called mass timber) often performs better than concrete or steel in both fires and earthquakes, a big plus when building in the Western U.S. And building codes are now being revised to reflect these attributes, allowing for taller timber buildings in American cities.

For architects like Anderson, CLT also opens the door to new ways of practicing. “For the past 100 years, architecture has been marginalized within the construction industry, mainly for liability reasons,” he explains. “The manufacturers fabricated the materials, the architect made the designs, the engineer determined the structure, and then the contractor built the building.”

With CLT, architects enter the process at the beginning of the chain and play a major role in the entire process, from material manufacture to construction. Using 3D digital modeling software, the architect designs the prefabricated timber pieces down to the smallest detail as part of the overall building design process; these specifications pass directly from the modeling software to the software of a CNC router, which cuts the CLT pieces to size.

Everything is decided up-front by the architect, from joinery details to the order in which the panels will be delivered and assembled at the building site. “We were always really engaged in the sourcing of materials, manufacturing, design tools, and models,” says Anderson. “Now we do everything to the level of the builder.”

Yasmin Vobis and Aaron Forrest, principals of Ultramoderne who joined CED’s architecture faculty this spring, are also excited about how working with CLT impacts the practice of architecture. “Mass timber requires architects to get into the issues of construction and collaborate with fabricators and structural engineers at the outset of a project,” they note. “It opens up possibilities you might not consider just working in the studio with fellow architects.”

Anderson Anderson Architecture and UItramoderne have both been exploring the possibilities of CLT for a range of projects, including prefabricated modular housing. View some of their projects below.

Anderson Anderson Architecture

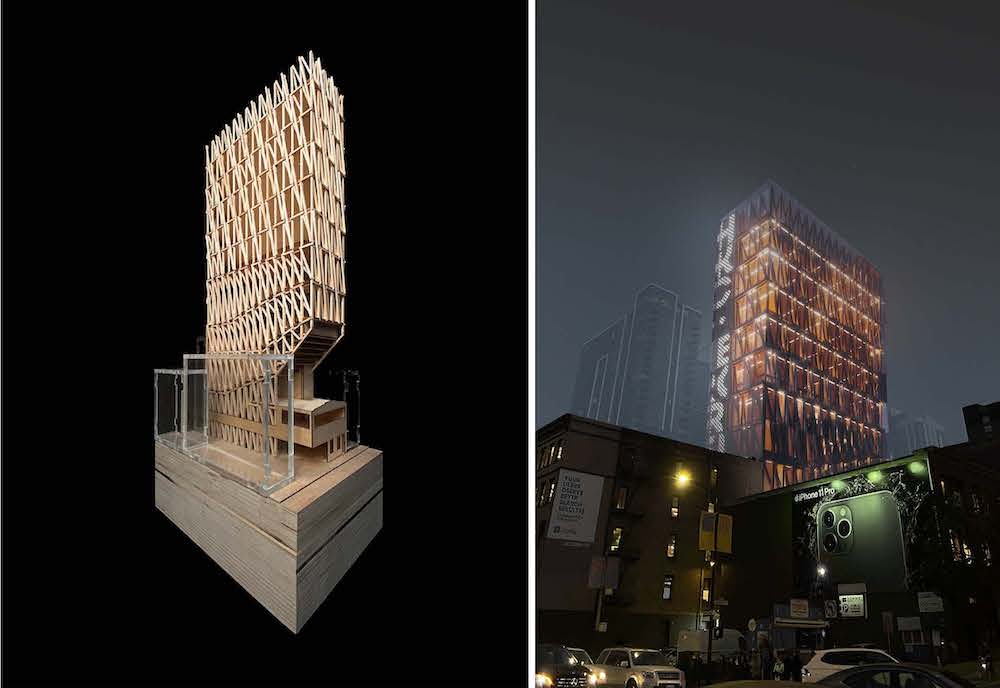

The Matchstick reveals its 12-story timber skeleton behind glazing as it rises like an urban stage from a network of small alleys in San Francisco’s downtown SoMa district. Recent code changes permit a timber building of this height; due to its use of CLT, the Matchstick is carbon-sequestering and fire-resistant, despite its name.

CLT structures tend to showcase material and structure, with exposed joinery. “There is more potential for expressive construction and so the architectural detailing tends to be more of a structural approach to architecture, rather than surface treatment,” says Anderson.

Expanses of exposed wood in CLT structures create a natural warmth. “People respond to these spaces, which feel humane,” says Anderson.

This mass timber version of a modular ADU, the first of its kind, is entirely prefabricated off-site at a factory space in Oakland, California. The entire structural module and primary enclosure is constructed with just six massive, cross-laminated timber panels: four wall panels, a floor panel, and a roof panel. The question of how to rationalize the construction process has been a driving question for Anderson since his early work on housing in Japan.

Ultramoderne

The radical horizontality of this lakeside pavilion gestures to the Chicago landscape and the nearby work of Mies van der Rohe. The prominent CLT roof floating on minimal supports — mass timber can span larger areas than traditional wood construction — becomes a new artificial horizon. “It looks very innocent,” says Forrest, “but no one had ever done CLT that way ever before. It works the way it looks.”

CLT is used monolithically here as both structure and skin. A series of CLT corners are recombined and stacked to create an unexpected labyrinth.

This prototype for a net-zero affordable duplex housing uses CLT structurally — to span a large, open volume — and to create a naturally efficient thermal enclosure.

Top image: Anderson Anderson Architecture, The Matchstick, San Francisco. Rendering of interior performance space.