Graduate students propose innovative solutions to California’s housing crisis

CED’s interdisciplinary Boyce Housing Studio takes on housing element sites in Menlo Park and Piedmont.

“Saying ‘no’ to housing is no longer an option in California,” asserted California Assemblymember Buffy Wicks, who represents the East Bay and is chair of the Assembly Housing Committee. She was addressing an audience who had gathered for the James R. Boyce Housing Studio Symposium at the College of Environmental Design (CED) to hear graduate student proposals for building housing in Menlo Park and Piedmont.

Since 2017, the interdisciplinary Boyce Housing Studio, funded through a generous gift from James R. Boyce (MArch 1967), has been bringing together CED graduate students in architecture and city planning to focus on affordable housing. The interdisciplinary studio, which now includes students from the college’s real estate program (MRED+D), culminates in the annual symposium, where expert jurors select winning projects.

In past years, the studio explored how to develop housing on state-owned land through public-private partnerships. This year, the new policy context in California provided an opportunity to work with cities as they initiated plans to allow for significantly more housing. Because of a series of newly enacted state laws, these plans, or housing elements, are more ambitious than in previous years. Cities are required to identify viable sites, create higher housing targets, and zone for much more affordable multifamily housing than in years past.

New policies encourage construction of affordable housing

“This was the exact right moment for this studio to tackle the question of how smaller California jurisdictions, which have traditionally been single-family only, might open up their communities for denser affordable housing,” says the studio’s co-instructor Ben Metcalf, managing director of the Terner Center for Housing Innovation and adjunct professor in City & Regional Planning. “Cities in California are committing to new housing elements, which for the first time will be meaningfully enforced by the state, but they don’t yet know how to meet these commitments, specifically around the rezoning of city-owned lots for multifamily housing.”

At a time when experts haven’t yet wrapped their minds around how to develop these city-owned parcels according to new state regulations, students had the opportunity to be at the leading edge of solving California’s housing crisis.

Graduate students worked in interdisciplinary teams to develop detailed proposals for affordable housing in either Menlo Park or Piedmont. Both of these Bay Area towns are affluent and historically exclusive, but their leadership was eager to work with the Boyce Studio to explore ways to incorporate affordable housing into their communities. The proposals included a narrative that articulated an overall vision, a master plan, financing and phasing details, and designs for individual units of housing and supportive services.

“The work they did in this studio is incredibly relevant, not just to Menlo Park and Piedmont but to cities across the state. Students tested the theory of the case: Is it possible to build affordable housing in this new policy context?” says Metcalf.

Challenges of the housing element locations

When asked what her team’s biggest challenge was, Holly Armstrong, who is in the Master of City Planning (MCP) program, didn’t hesitate: “parking.” She was on a team with two other planning students, one real estate student, and one architecture student who worked on the Menlo Park site. The location the city selected is a series of city-owned parking lots in the downtown area; they want to build 345 affordable housing units but don’t want to lose any surface parking spaces.

But the team, who proposed The Menlo Collaborative, had met with the mayor, city council members, city planners, and the chamber of commerce and was encouraged to hear that the city was open to new approaches. They aimed to convince officials not to retain all of the parking, especially since the site was next to a CalTrain commuter rail station.

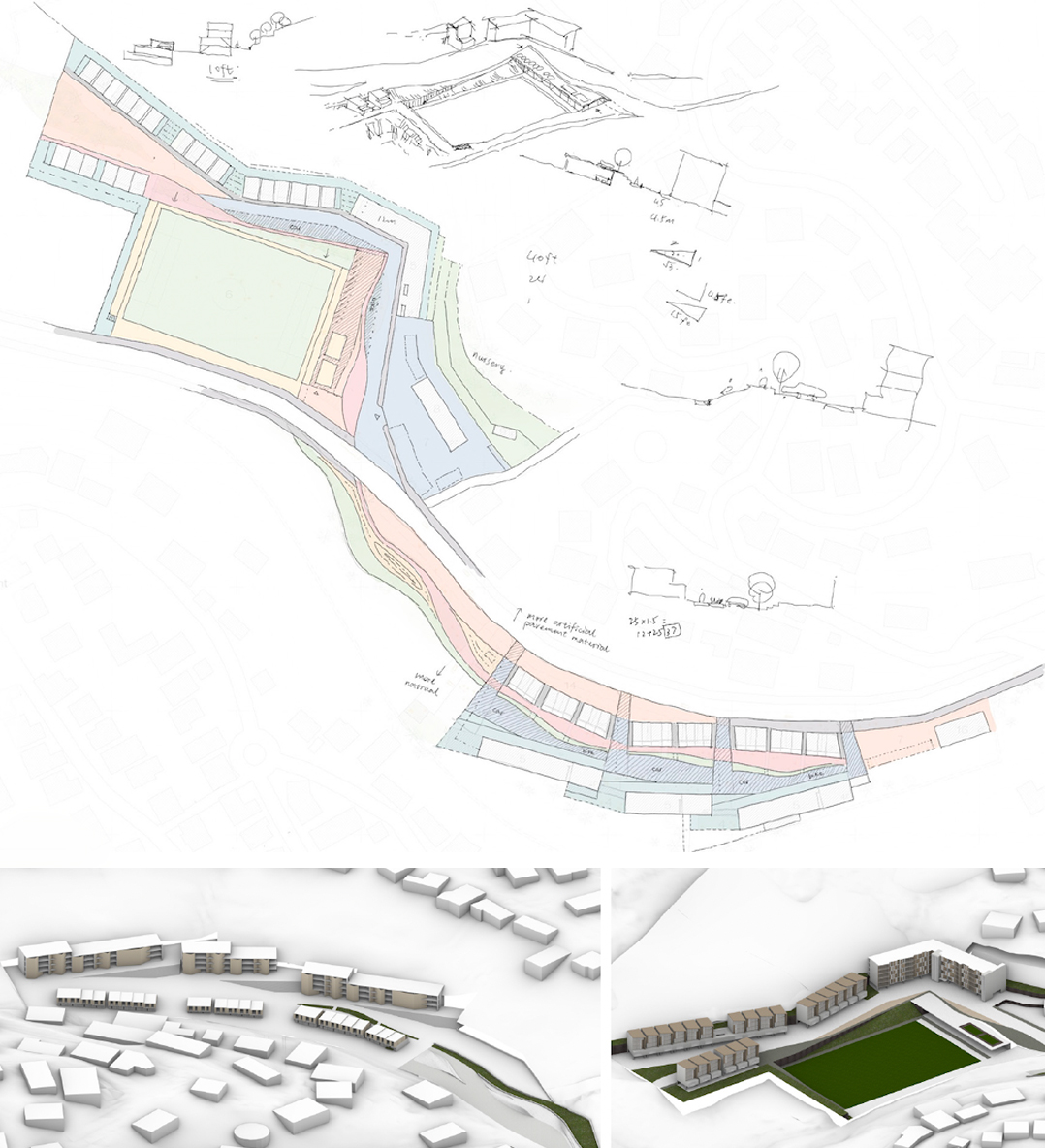

The challenge for the students working on the Piedmont site, in Moraga Canyon, was topography. The walls of the ravine site are steeply sloped, and even the canyon floor is not level. One of the teams working on this site adopted the idea of building into the slope, looking to the iconic slanted-roof houses of Sea Ranch, designed by UC Berkeley architecture professors in the 1960s, as a precedent. “We can maintain a low-rise volume at the street, creating a human-scale pedestrian neighborhood spine,” explained Brittaney Bluel and Todd Liu, the two MArch students on the team, “and then gain height and density toward the back of the lot.”

Pushing change through creative design

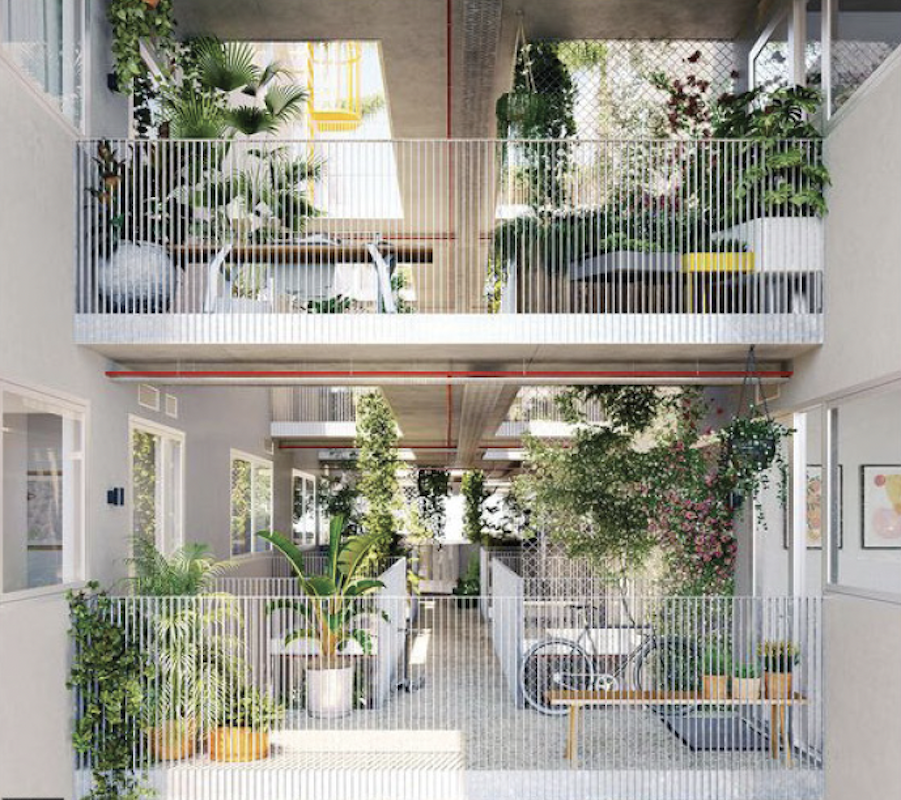

Working on actual sites and within real-world constraints pushed the students to find other innovative solutions. The PAAD team working on the Menlo Park site leaned into the idea of using single-stair circulation, anticipating the passage of proposed state legislation that would eliminate the mandate for two means of egress for multifamily residential buildings. “That allowed us to use space more efficiently, so we could propose medium-height construction that relates to the existing urban fabric,” said Jono Coles, one of the MArch students on the team. “The square footage that would have been used for interior circulation can be allocated instead to shared outdoor spaces.”

Like Armstrong’s ’s team, the PAAD team also pushed back on the city’s desire to retain surface parking. They proposed delaying the construction of a parking structure to a later phase, allowing time for the community to get used to using public transportation, and designed a transit hub with shared cars and scooters. “Our proposal is rooted in the real world, but it is more aspirational. We’re using the master plan to push change at a time when Menlo Park might be open to trying new approaches,” said Kate Ham (MCP) and Reena Zhang (MRED+D).

Student proposals make an impact

“We really began to understand how the affordable housing system works,” said Chiara Noppenberger, an MArch student who worked on the Menlo Park site. This has been the aim of the Boyce Studio from the outset. The studio accelerates professional development in affordable housing and often sets students on their career paths. “Many alums of the studio are now movers and shakers in the California community housing spacing,” says Metcalf. This year, many of the studio alums returned to CED for the Boyce symposium as panelists and jurors.

At the end of the semester, teams had the opportunity to present their final proposals to the Menlo Park and Piedmont city councils. As the Piedmont Exedra newspaper reported, city council members were excited by the possibilities they saw in the Moraga Canyon proposal. Mayor Jen Cavenaugh said she had hoped to see a vision for that area, but that the council got much more than that.

The student projects will help each city make the case to residents for developing affordable housing at these sites. They will also inform requests for proposals (RFPs) that Piedmont and Menlo Park plan to issue to developers as they seek to fulfill their housing elements. Armstrong concluded, “We feel like we really had an impact.”