Expanding the Circle of Normal: Chris Downey on Universal Design

Chris Downey is the inaugural Lifchez Professor of Practice and Social Justice at UC Berkeley’s College of Environmental Design, teaching a studio that continues the work of Professor Emeritus Ray Lifchez, a trailblazer of universal and disability design.

Downey is a blind architect who practiced architecture for decades before losing his eyesight. Today, he’s finding new ways to pursue architecture and advance universal design. He also took up rowing after becoming blind, and the sport has become for him a metaphor for inclusive design.

“It is one of the only truly inclusive sports,” states Downey, “As a blind athlete, I can be on a crew team without any adaptation or accommodation. I have enough information through a multisensory experience of feeling the boat’s motion and set, hearing the blades catch the water, and sensing the rhythm to be fully included.” It is also a team sport—“Getting in the boat—and rowing together.” That could be the other side of the metaphor: merging tactility and multisensory experience with human connection and teamwork.

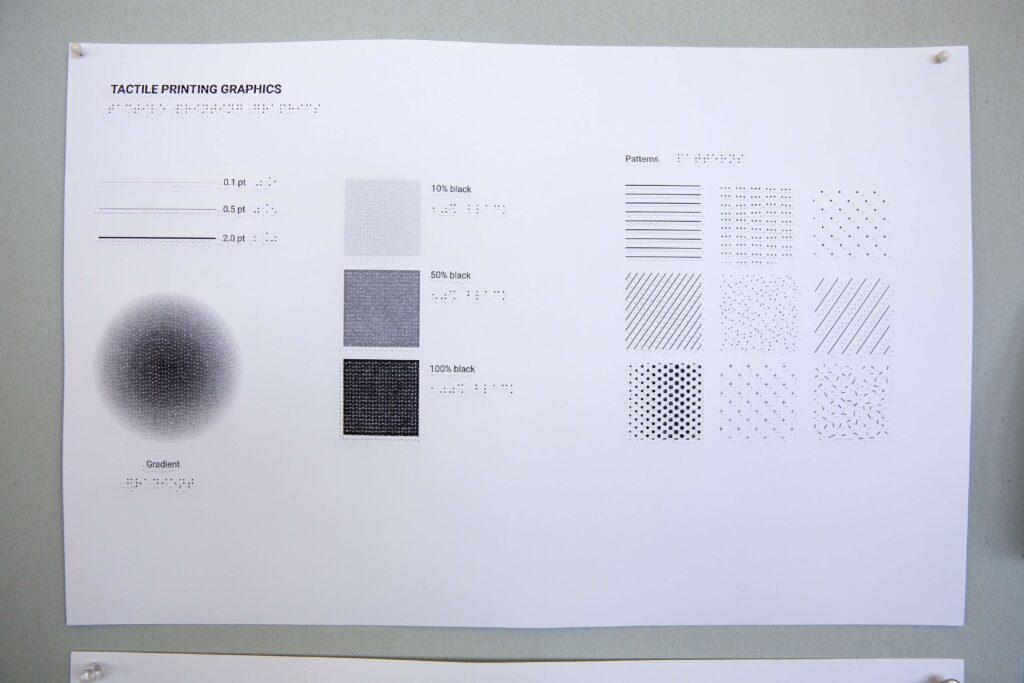

On the last day of spring semester, students presented their boathouses before their final with guest reviewers. Each of them sat down with Downey to guide him through their designs. Throughout the process, Downey ran his hands over the tactile plans, asking the students questions as he moved through the space. In this studio, the plans were 3-D printed in braille. The class created standards for features that especially impact people with low vision, for instance, communicating contrasting light gradients and color by varying densities, hatch patterns, and heights on the page.

When Lifchez, who sponsored the studio, joined the class, the students gathered around a large table in the pin-up area. The students began by sharing their experiences. Time and again, they exclaimed, “I will never look at design the same way again.”

Downey introduced the final project as an inclusive community boathouse adapted to integrate people with disabilities and different life experiences into the sport. “I am much more excited about designing spaces that connect people and communities than designing separate or special places for people with disabilities,” he says. In place of the current boathouse, “essentially a garage,” the new boathouse will include an indoor rowing tank, allowing people with disabilities or who are not yet comfortable with rowing to gain confidence. There will also be spaces for study and non-profits doing education training and life support services.

“This is not about code obligations or assuming that people with disabilities or from the broader community won’t do this or that task. The assumption here is that they will do any or all of these things, so let’s operate from there,” says Downey.

The boathouse’s location on the water and the Bayfront Trail led Erika Blandon, a graduate student in the M.Arch program, to make the focal point of her design an adjacent pavilion providing underserved youth with access to kayaks, bikes, and boats. An adaptive sports space, where equipment can be altered for different needs—part of what Downey calls the Adaptive Realm—joins the two buildings. “The studio made me more conscious of how to design for everyone, in a way that doesn’t limit anybody,” says Blandon.

Carmen Carretero Martinez’s boathouse incorporated a translucent façade, materials, and acoustic canopies to aid people with lower vision navigate the building. The sloping roofs distribute water from boat washing through the park. Will Rundquist’s model had a long bar running from the park through the boathouse with a central opening to the boat plaza, docks, and water. Ramps and slopes connected the water, boat bays, and program areas above. He also incorporated a rich material pallet and acoustic strategy for the blind experience.

“Our students today want to contribute to social justice, on all sorts of levels,” says Downey, making a link between social justice and sustainability. “Just as you don’t want to waste resources or use practices that are detrimental to the environment, you don’t want to design places that exclude and thereby minimize the value, contribution, participation, and integration of people you might not otherwise think of as just another person there next to you.”

Having a baseline understanding in the studio of concepts like equitable use was helpful, says Downey. The idea, for instance, that “you could have steps here and an elevator elsewhere in the building, but does that create an equitable experience?” The principles of Universal Design function like questions, nudging you as you work, “Well, did I do that? Is this equitable?”

Downey points out how disability design is often thought about in terms of accommodation, “which is important,” he adds—though it can lead to elevator-and-stair type solutions. More interesting to him is how designing for universality not only promotes inclusivity for disabled people, but can reveal things that benefit architecture and design education more generally. “The hope is for students not to see it as regulation, but to find and revel in the opportunities for creativity,” adding nuance to their understanding of architecture.

Design for Downey is about centering the individual human experience within an environment and being mindful of the needs, desires, and experience of whoever that person might be. That human-centered focus “ties back to how Ray Lifchez approached his studios.” It is also something he found reading tactile plans. “Reading plans in tactile form puts me right there in the space, triggering in my mind all the elements we are working with—the sun coming in through the window and touching your face, the sound of materials underfoot, or of the textures around you and their thermal and olfactory qualities, as well as the experience of memory.” In tracing the plan, Downey is also building a mental map to see: “Can I hold it in my mind and navigate the space with confidence?”

Designing for universality involves thinking about spaces from different points of view: What is it like to see and engage with a space if you are seated in a wheelchair? “Likewise, if you are blind, what makes a good, rich, engaging environment, and how can that add to the experience for everyone else?” To help students with some of those questions, Downey continues a practice Lifchez initiated in the 70s to bring people with different backgrounds and disabilities in as clients. “The more we engage and work with others, the more we collaborate with clients or users, as Ray Lifchez would do, the better the work is,” says Downey.

For Sabin Ciocan, the studio and the process of tactile printing and more hands-on modeling was an opportunity to rethink the design process and representation. “It becomes more about the process and how your drawings and models communicate, and a chance to see how the concept manifests for everyone.”

“One thing I have come to value and try to share with the students is that gaining a disability late in life opened me to an entirely new community of people that I didn’t have the benefit of knowing before. Design for me is about expanding the circle of what is normal and recognizing that disability isn’t about somebody else; it is inherently about the absolute reality of the human condition.”

“There is only one way to row,” Downey says, “by getting in a boat with people and rowing.”