Danika Cooper uses tools of landscape architecture to visualize a decolonized U.S.

In new research, Danika Cooper, associate professor of landscape architecture & environmental planning explores how drawing and mapping — the graphic tools of her discipline — can provide actionable strategies toward an anticolonial, antiracist future. She demonstrates that these methods of visual communication can both document Indigenous dispossession and make claims for land-based reparations.

“I hope to show the very real ways that the design disciplines can contribute to creating just futures that consider the intersections between history, place-making, and racial structures,” Cooper says.

The research appears in the Journal of Architectural Education article “Spatializing Reparations: Mapping Reparative Futures,” which was just named the 2024 Best JAE Essay by the Association of Collegiate Schools of Architecture.

Cooper subverts the traditional purpose of mapping land in the U.S. during the era of settler colonialism. Instead of cartography as a tool of territorial conquest and genocide — a method of converting land into property — she reenvisions mapping as a way to empower dispossessed Indigenous peoples.

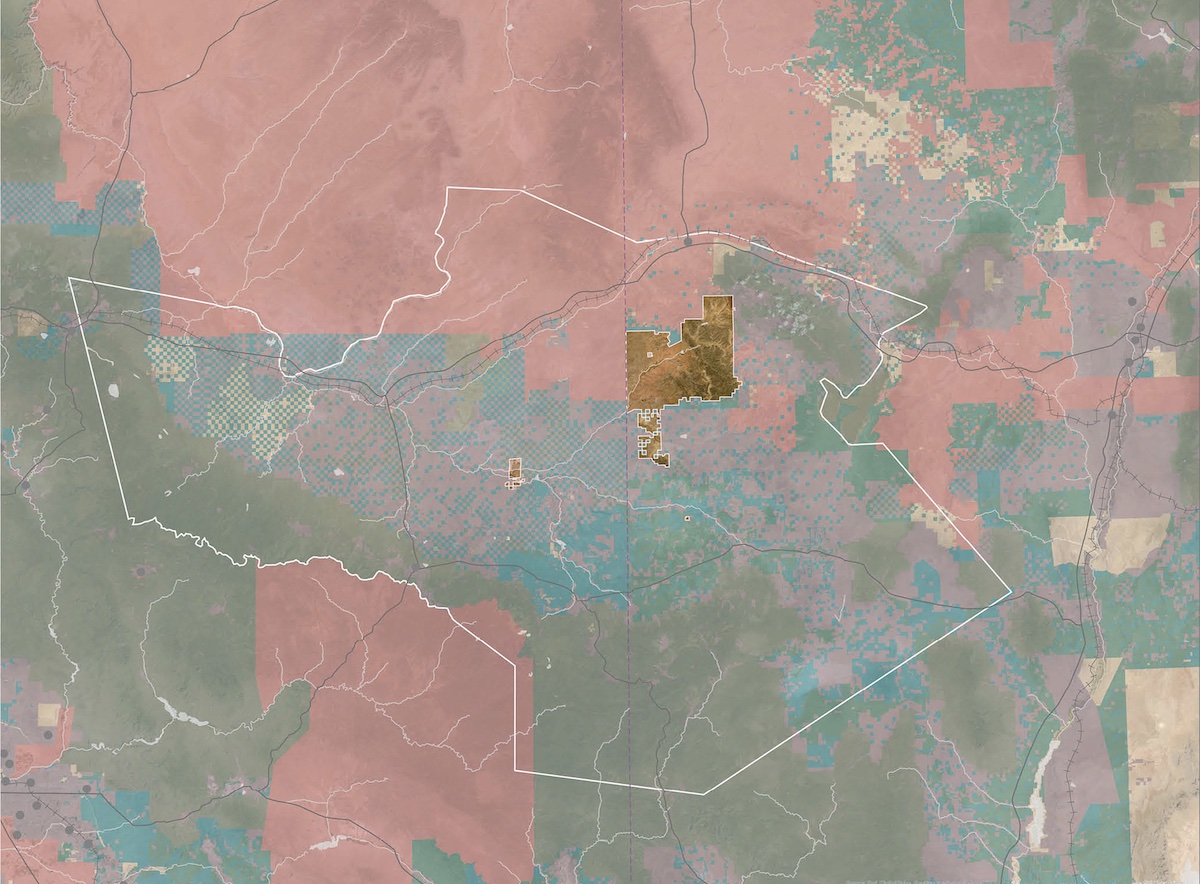

“I believe that visualizing the specificities of place can support expanded engagements with land in ways that benefit Indigenous peoples in the United States,” she says. For this project, Cooper focused her research on the A:shiwi (Zuni) in the American Southwest and the Tongva, in the Los Angeles metro region.

She used traditional cartographic methods to show proof of territorial dispossession. For example, her maps documenting the diminishing boundaries of A:shiwi territory over time powerfully reveal historical truths.

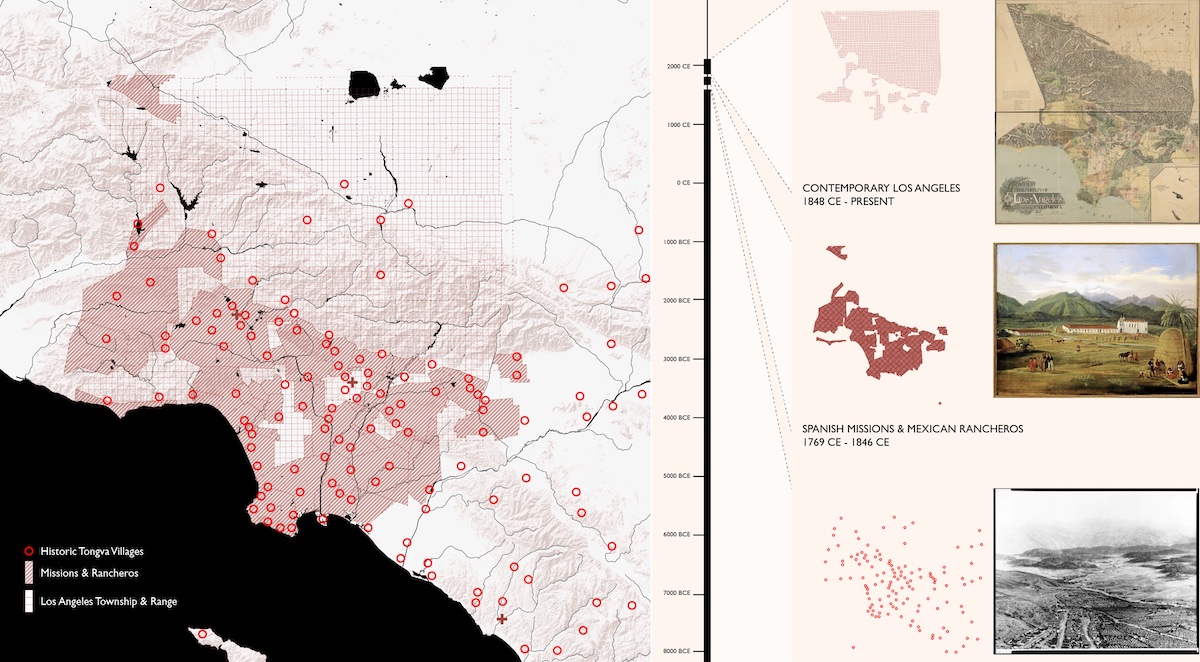

To express non-Western ways of engaging with land, Cooper turned to more innovative representational techniques. Her drawings overlay multiple viewpoints, perspectives, geographic scales, and time periods to create more complex readings of land that resonate with Indigenous ways of understanding a connection to place.

For the Tongva, who are not federally recognized, for example, Cooper used maps and drawings to reinscribe them into the urban landscape of Los Angeles and challenge prevailing narratives of extinction. She mapped significant Tongva sites throughout Los Angeles County over time, illuminating the ways that Indigenous peoples have continued to shape the city.

Cooper believes that these strategies of representation can inform rematriation of land back to Indigenous peoples, communities, and nations, “redrawing the United States landscape as literal ground for Indigenous sovereignty.”