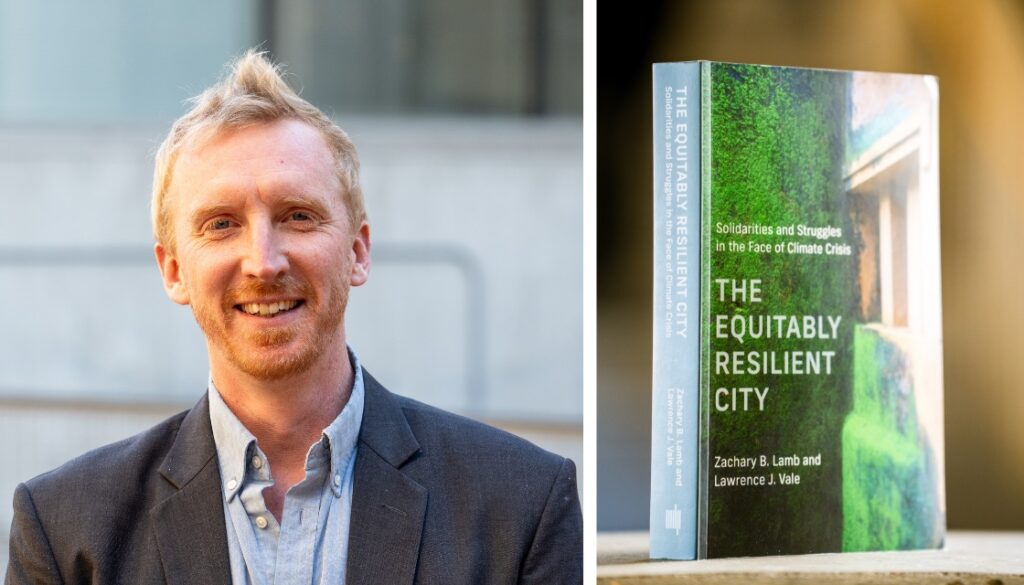

New book from Zachary Lamb on making cities climate resilient and socially just

NAMED 2025 BEST BOOK IN URBAN AFFAIRS BY THE URBAN AFFAIRS ASSOCIATION

The Equitably Resilient City proposes a framework for planners and designers pursuing climate resilience strategies that strengthen and empower vulnerable communities.

As scenes of devastation wrought by hurricanes in North Carolina and Florida, flash flooding in Spain, and a typhoon in Taiwan deluge our screens, there is no question that cities around the world need to adapt to avoid the most violent effects of a rapidly changing climate.

The Equitably Resilient City: Solidarities and Struggles in the Face of Climate Crisis (MIT Press), a timely new book from Zachary Lamb, assistant professor of City & Regional Planning, and Lawrence Vale, associate dean and Ford Professor of Urban Design and Planning at MIT, asks, “How can planners and designers help vulnerable communities build the power to act in the face of climate change?”

“Planners are increasingly focused on shaping cities that are resilient to climate change. But the word ‘resilience’ can imply that disaster-struck cities should ‘bounce back’ to the way they were before. Our book makes the case that ‘bouncing back’ to an unjust status quo is not enough,” says Lamb.

“Many of the people and neighborhoods most imperiled by climate change also face a range of other forms of disadvantage and marginalization,” he notes, citing residents of Brazilian favelas, Texas manufactured home parks, and self-built informal settlements in India. “How can cities adapt to climate threats, like excessive heat, flooding, and landslides, without displacing or further disadvantaging these communities?”

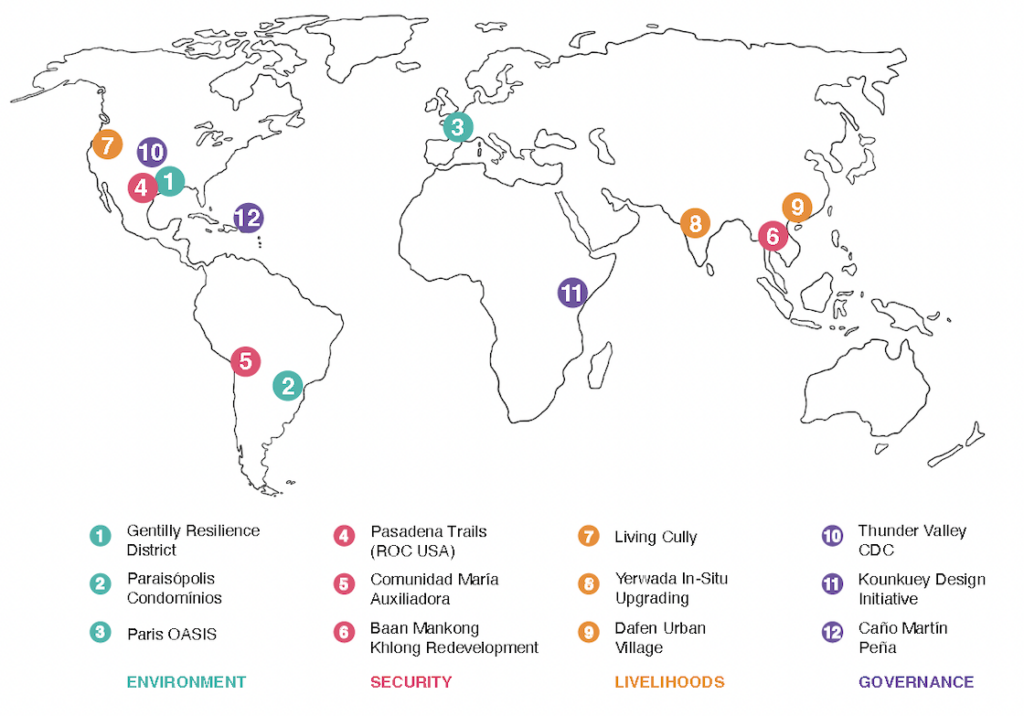

Focusing on 12 case studies from across the globe — representing different regions, settlement types, scales, climate threats, and approaches to resilience — the authors offer concrete strategies for equitable urban resilience. The case studies are organized into four categories, each representing a principle for creating equitably resilient cities: environment, security, livelihood, and governance.

Reducing environmental vulnerability in New Orleans

The authors address urban flood resilience in several geographic locations, including Gentilly, a working-class, majority-Black New Orleans neighborhood built on land reclaimed from wetlands. As a case study of the environment principle, the authors investigate the Gentilly Resilience District, which was initiated after Hurricane Katrina to implement strategies to live with water, rather than resist it.

The plan calls for accommodating stormwater within the built environment, in new parks and daylit canals, under playing fields, and along designated streets. By making the flow of water through the neighborhood more visible, the project also helps the community better understand the water dynamics of their everyday landscape.

Securing housing along flood-prone Bangkok canals

Lamb and Vale interpret security, their second principle of equitable urban resilience, as security from displacement and other forms of violence, recognizing that urban renewal in the name of “security” in the past has often resulted in the uprooting of communities.

The book presents Bangkok’s “people-driven” Baan Mankong program as a case study in this section. Migrants to the city living in unsanctioned, self-built structures along the city’s canals were vulnerable to flooding and polluted water, as well as eviction. The authors show how through collective saving and land ownership, participatory planning, and self-governance, thousands of homes were rebuilt to resist flooding and improve sanitation. Residents, now collective owners, are protected from eviction and invested in maintaining and upgrading their neighborhood.

Building environmental wealth in Portland, Oregon

In the section on livelihood, the authors spotlight a coalition of NGOs working in the low-income Cully neighborhood of Portland, Oregon, which is threatened by industrial pollution and extreme heat. Living Cully aims to fight poverty and displacement due to gentrification while making the neighborhood healthier.

Its programs link the development of green infrastructure, open space, and home weatherization to job training and living-wage employment opportunities in environmentally progressive industries. “Forging dignified livelihoods is at the core of Living Cully’s concept of environmental wealth and thus at the core of their pursuit of equitable resilience,” Lamb and Vale write.

Empowering vulnerable communities in Puerto Rico through inclusive governance

In the final section, focusing on governance, the authors show how involving communities in the planning process and empowering them with ongoing tools for self-governance can be important for long-term resilience and equity. One chapter focuses on the neighborhoods flanking the Caño Martín Peña in San Juan, Puerto Rico, a tidal estuary threatened by sea level rise and increasingly frequent and intense tropical storms and hurricanes.

Local community organizations, wielding legal power granted by a newly enacted law and united as a community land trust, partnered with government agencies to ensure that improving drainage and reducing flood risk “would not also wash away the thousands of low-income residents.” The community-driven project resulted in thousands of residents being rehoused at a safe distance from the waterway, but still within their community.

Discussions of resilient urbanism often oscillate between rosy boosterism and doom-laden critique, Lamb notes. “We are trying to offer a path between those poles, focusing on ‘partial successes’ that offer promising models as well as warn of some pitfalls,” he says. Ultimately, Lamb and Vale hope to offer models for community leaders and professional planners to draw on as they tackle the twin crises of our time.